Glacier Upsala, on the northern arm of Lago Argentino and within the Los Glaciares National Park is one of the longest glaciers in South America. It is 60km when measured end-to-end and is one of the largest and most powerful glaciers in the region. It is also one of the most fragile.

The Southern Patagonian Ice Field is the engine that powers Glacier Upsala. The ice field is the largest non-polar ice mass on earth and a remnant of a huge ice sheet that covered all of Patagonia during the Ice Ages. It acts like a frozen reservoir with the snow that falls onto the plateau compacting into firn and then glacial ice. Gravity pushes the ice outward in all directions, draining through major outlet glaciers into valleys, fjords and lakes. Upsala is one of these outlets – and one of the largest and most important on the Argentinian side of the ice field. The glaciers upper section is directly attached to the main ice field so its flow rate, mass balance, thickness and retreat/advance pattern are tied to conditions on the plateau – especially snowfall and air temperature. If the ice field thins or warms, outlet glaciers like Upsala respond rapidly. Upsala is one of the fastest retreating glaciers in the region – a signal of the changing climate of the ice field, and a bellwether for other east-flowing glaciers.

Our day trip started with a one and a half hour drive to Puerto Punta Bandera along the shoreline of Lago Argentino. The lake is a bright turquoise from all the silty meltwater, deposited by the main glaciers that feed the lake. And the Patagonian steppe (known as Pampas to the locals) stretched off into the east and the snow-capped Andes rising to the west. We hopped on a modern catamaran that can hold around 90 people to make our journey up the North Arm of the lake to the glacier.

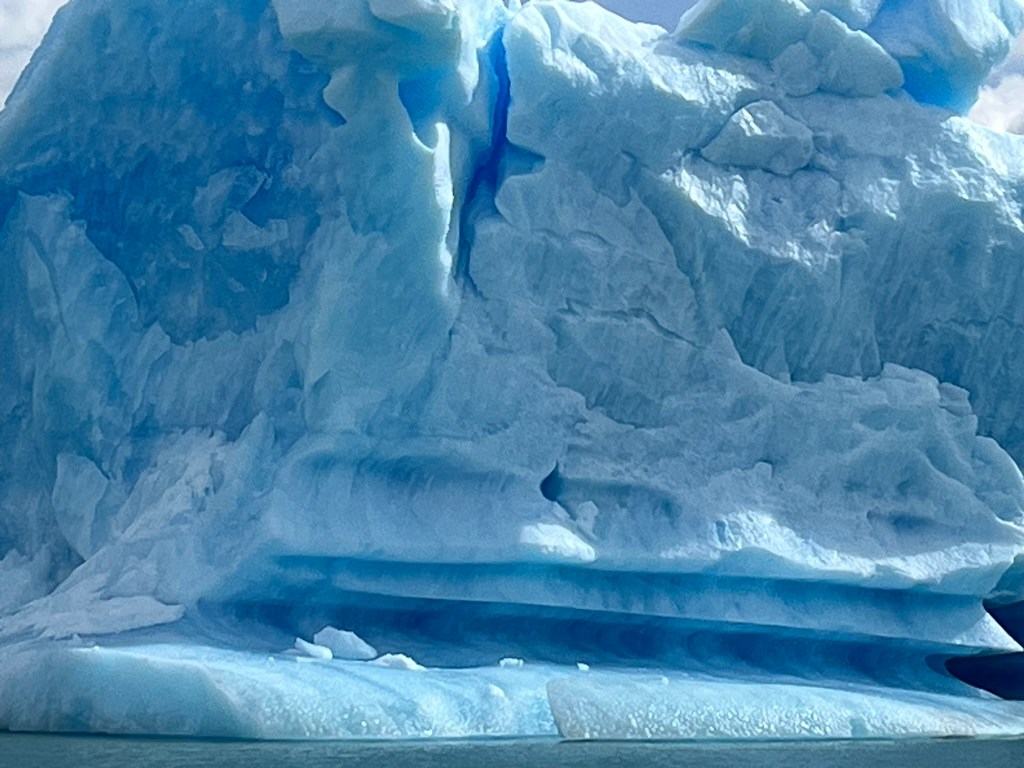

The scenery quickly becomes more dramatic, with the mountains getting taller and their peaks sharper. Glacially carved walls, remnants from ancient gigantic glaciers can be seen on both sides of the north arm. You start seeing small icebergs floating along almost immediately after leaving the port but after about 45 minutes is when the huge icebergs start appearing, and in big numbers. The colors range from electric to deep blue, crystalline white and bright turquoise. Some of the icebergs are taller than houses – and that’s that only the bit visible above the surface of the water. 90% of an icebergs mass is under the water.

We reached the branch of the lake that heads to Upsala Glacier but only to a safe viewing point 5km away from the glacier face. Further up the branch there is a massive iceberg field which would be unnavigable for the catamaran and with the size of the chunks of ice calving off the front of the glacier, it is just too dangerous for boats to get any closer. After taking photos of the glacier itself we spent about 45 minutes weaving in and out of different icebergs admiring their color, shapes and the different ways they have melted. The blue of the compacted ice is so intense.

Then we continued northward leaving the iceberg field and entering Canal Cristina. This area is quieter and narrower with sheer rock walls rising on both sides. As you disembark its hard not to feel like you are an explorer arriving in a remote frontier outpost.

At Estancia Cristina we jumped in 4×4 trucks, each holding about 12 people, and started the hour-long drive up to the Upsala Glacier Viewpoint. You can only access this view point through joining a day trip run by Estancia Cristina. The terrain is rugged and you climb up slowly through the glacially carved rock, over moraines and up to the high plateau.

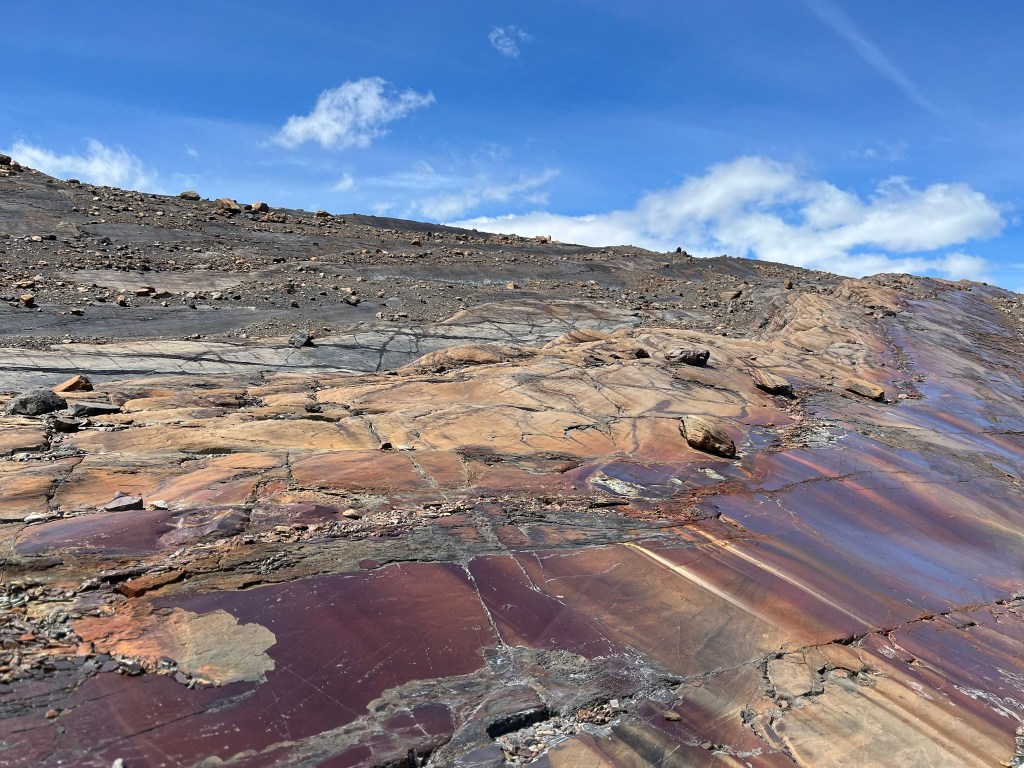

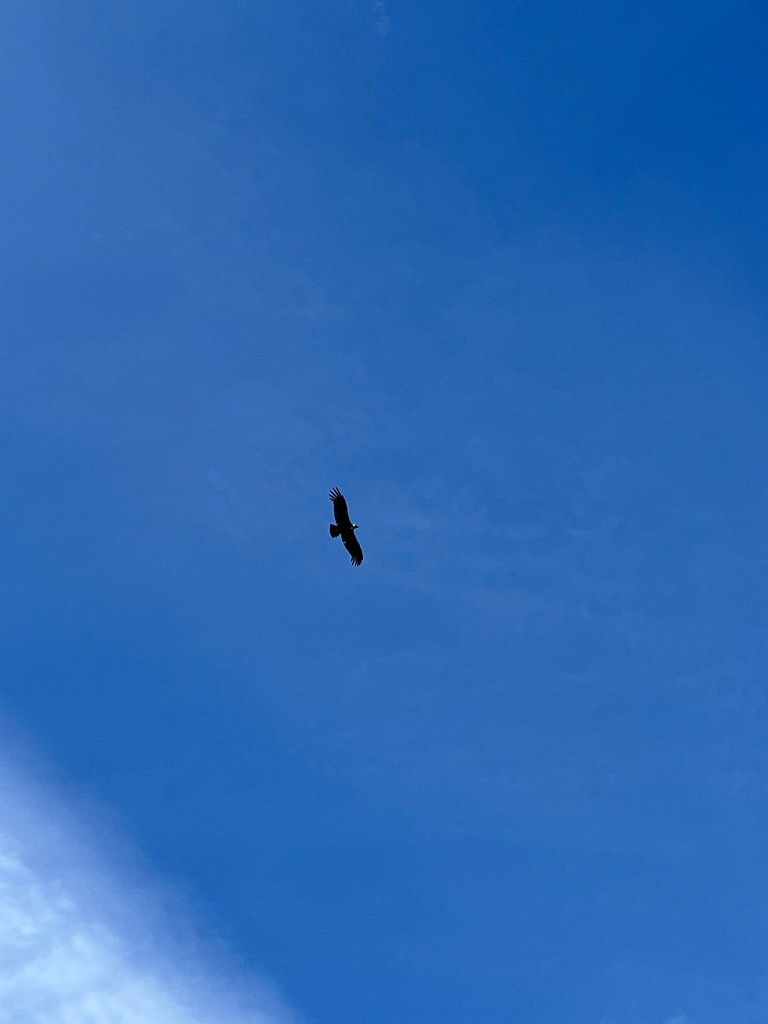

The final part of the journey to the viewpoint is by foot along an undulating path of striated bedrock slabs. This region is not volcanic, everything here is old continental crust that has later been shaped by glaciers. The metamorphic rock is hundreds of millions of years old and belongs to the Patagonian crystalline basement which formed deep in the earth’s crust before being uplifted and later overridden by ice. The walk is spectacular, and its easy to see direct evidence of glacial abrasion with long grooves carved into the rocks and smooth shiny surfaces. And in all sorts of shades of browns and reds, reflecting the different mineral compositions in the ancient folded layers. We were also treated to three enormous condors flying overhead.

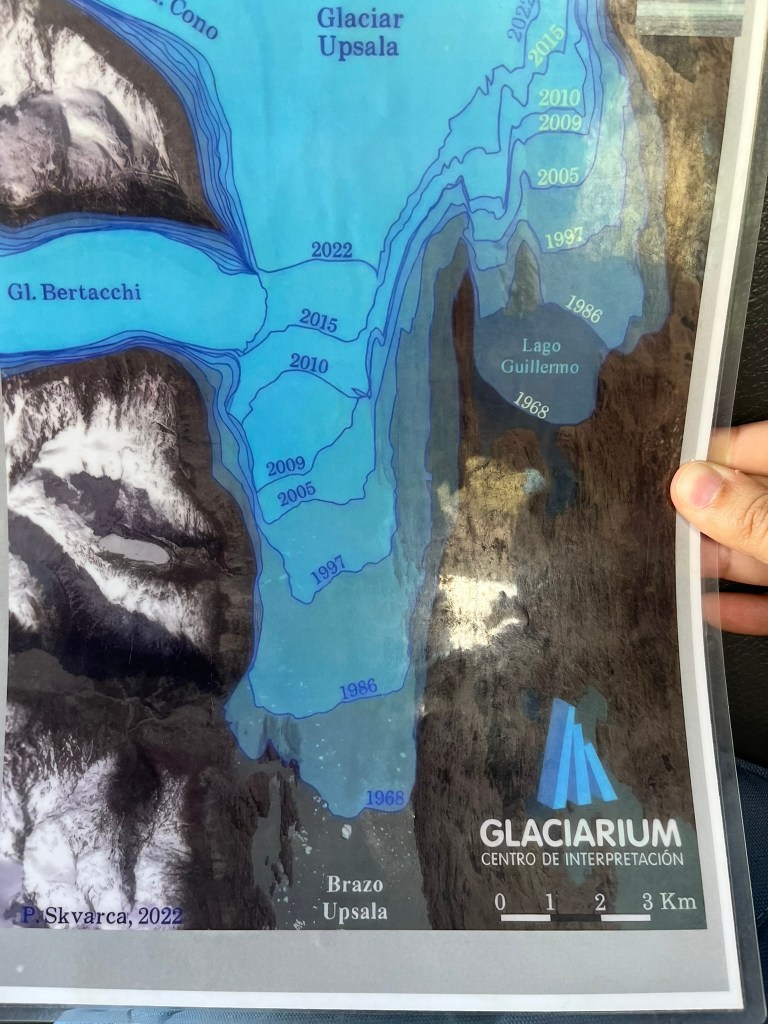

The walk takes about 15 minutes at an average pace and you are rewarded with a perfect view across the entire Upsala Glacier Valley. The glacier once filled the whole basin. As the glacier has retreated it has revealed the exposed terrain beneath this gigantic wall of ice, including Lago Guillermo directly below the view point, where icebergs still drift. Its another otherworldly view – of the many I have already had in my time in Patagonia. And absolutely worth the trip.

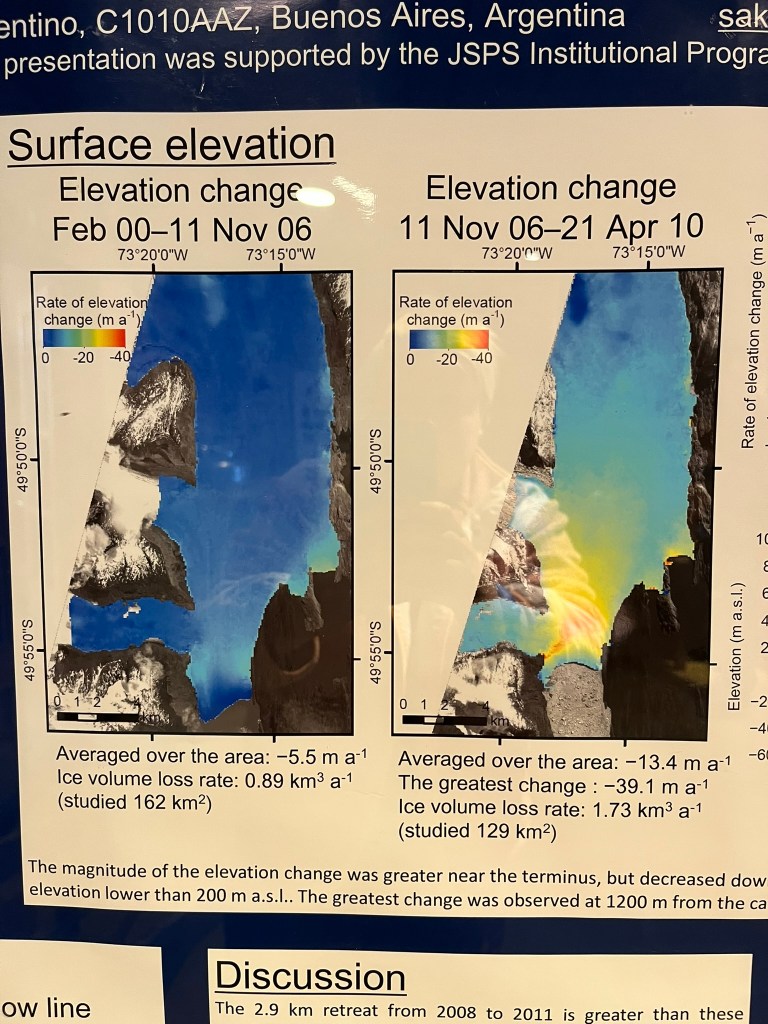

Upsala’s retreat over the past 100 years is one of the largest seen in the Southern Patagonian Icefield. In the early 1900s the glacier filled most of the current fjord. From the 1970s to the 2000s there was a major acceleration in its retreat. And from 2010 to present, the glacier has broken into multiple tongues and experiences near constant calving. The front of the glacier has retreated many kilometres since the mid-20th century.

Upsala is a lake-retreating glacier. This means that its front end sits in deep water, not on land. When an ice face is floating, or partly floating, lake water undercuts the ice, triggering calving events. Calving causes the glacier front to collapse backward and over time become shorter and thinner. Lago Argentino has relatively warm surface water in Summer. This warm water eats away at the submerged part of the ice front causing large slabs to break off. Because the glacier sits over a deep basin carved far below sea level, the ice front is actually retreating into deeper and deeper water over time. This causes a positive feedback loop whereby as the glacier retreats, more and more of the glacier becomes destabilised, and calving increases even more. This is known as marine ice cliff instability.

Satellite data shows that Upsala has lost tens of metres of thickness in some areas over the last decades. This also causes a feedback loop as thinning ice means less downward pressure within the ice resulting in more calving and faster retreat. The tributary glaciers that feed Upsala are also thinning and retreating, meaning that less ice is entering the central trunk. Climate change is amplifying all of this. In Patagonia, air temperatures have risen significantly over the past century. This means there is more melting on the glacial surface and more meltwater is draining under the ice causing the glacier to slide towards the ice front at a faster pace, all resulting in accelerated flow and calving. Upsala is especially sensitive to this because of its lake-terminating position.

After enjoying the fantastic views of the glacier we headed back down to Estancia Cristina, where we were treated to a 3 course meal and a tour of the old farm to understand the important history it has played in this region. Estancia Cristina was founded in 1914 by an English immigrant couple – the Masters. They arrived in Patagonia looking for grazing land and opportunity. The plot of land the were leased, with the promise of ownership after 30 years of farming, was located on this remote peninsula of what is now Los Glaciares National Park. I wonder if when they got the land they knew that over half of it was covered in a massive glacier!

Reaching the site requires navigating the Upsala arm of Lago Argentino and the early years of establishing the farm would have been very difficult, with limited access to resources, fierce winters, extreme winds and total isolation from the outside world. Despite this, the Masters family built one of the most successful sheep ranching operations in the region, raising thousands of sheep for wool export. The estancia became a symbol of pioneering life in southern Patagonia.

The Masters family lived at Estancia Cristina for five generations, maintaining the property long after most Patagonian ranches had mechanised or modernised. Eventually grazing in the national park became restricted and the family shifted its focus to conservation and tourism. Today it operates as a lodge, museum and the only route to the Upsala Glacier Viewpoint.

The trip to Glacier Upsala was absolutely fantastic and I’m so glad we included it alongside the more popular and accessible Glacier Perito Moreno, which we are going to tomorrow. This trip is only run by Estancia Cristina since they own the property through which you access the view point and there is only one boat per day that heads to the ranch, so if you are considering doing this excursion from El Calafate I recommend booking ahead.

Leave a comment