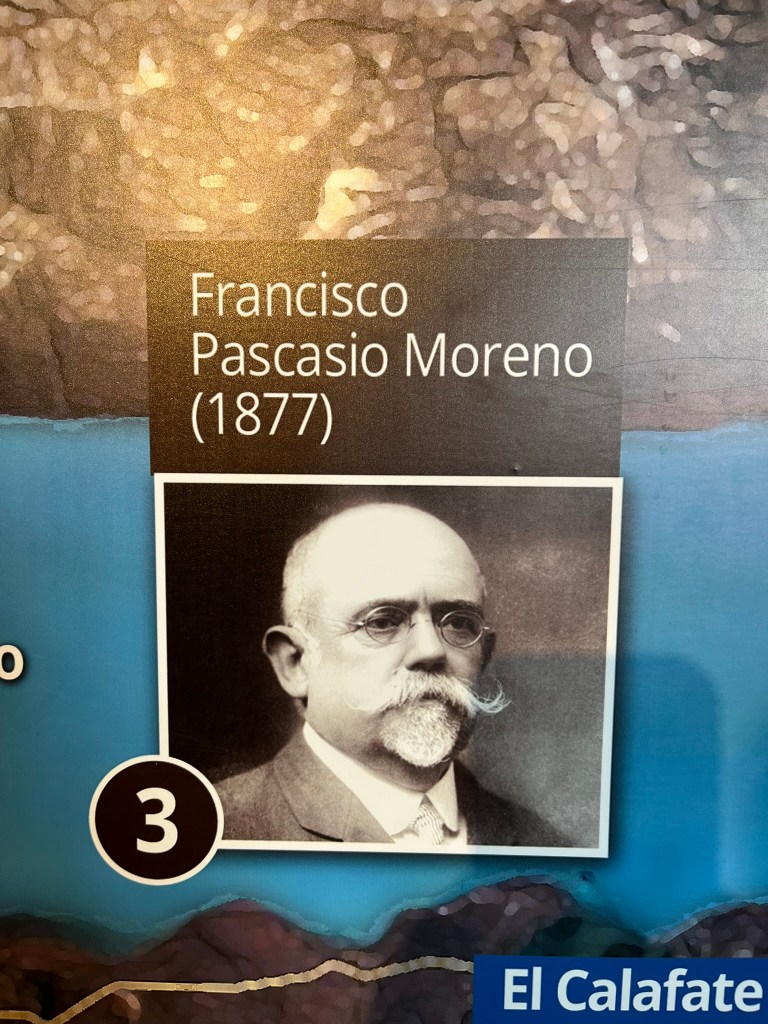

Perito Moreno is one of Patagonia’s most iconic glaciers. The glacier is named after Francisco Pascasio Moreno, a famous Argentine explorer who played a key role in surveying Patagonia and establishing Argentina’s national borders in the late 19th and early 20th century. His nickname was ‘perito’ which means ‘expert’ or ‘specialist’ in Spanish and several landmarks in Argentina bear his name.

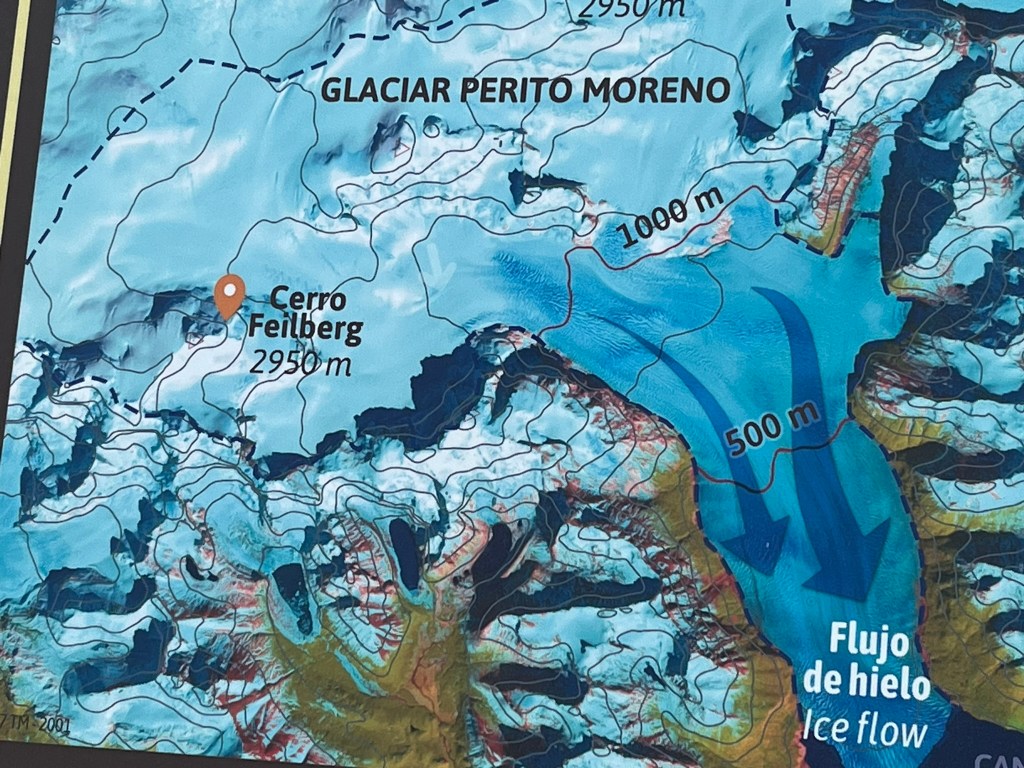

It is part of Los Glaciares National Park and sits on the southwestern arm of Lago Argentino. It is 30km long, 5km wide at the front and up to 70m high above the water line. Like Glacier Upsala it is also fed by the Southern Patagonian Ice Field. However, whilst Upsala is rapidly retreating, Perito Moreno is pretty stable. It advances and calves but generally maintains its position, although this seems be changing with significant retreat since the early 2020s. Also unlike Upsala, this glacier calves frequently but with relatively small to medium-sized events.

One of the most unique things about Perito Moreno is how accessible it is. It is by far the easiest glacier in Patagonia to visit. It takes an hour and 30 minutes to drive to the National Park from El Calafate. And from here you can access viewing platforms, boat trips and even glacial trekking. Today we would be taking a boat trip right up close to the glacier in the morning, and then in the afternoon we would be exploring the viewing platforms positioned on the headland closest to the glacier.

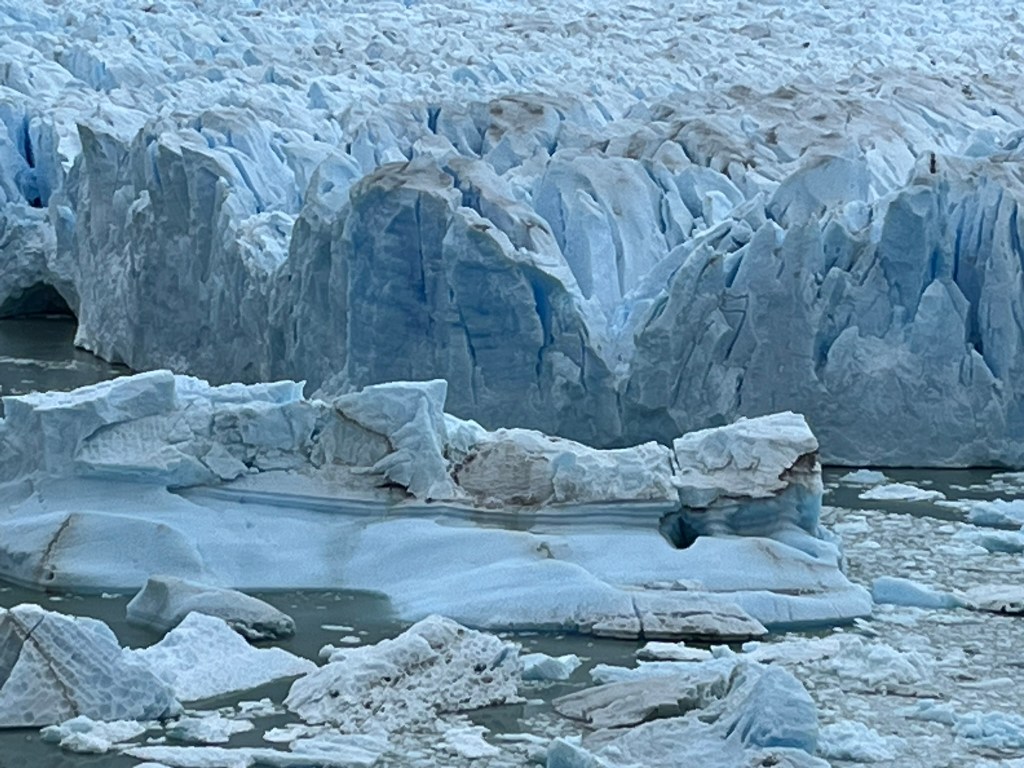

The boat trip out to the southern face of the glacier is excellent. The boat leaves from Puerto Bajo las Sombras and heads out to the dramatic and towering wall of the glacial front. The trip lasts about 1 hour and you spend about 40 minutes very close to the glacier – just a few hundred meters from the front. You can clearly see the heavily crevassed, jagged and fractured ice, with huge pieces leaning forward and looking like they could fall and collapse into the lake at any moment. You can here the noises the glacier makes – the cracking and groaning as the pressure of all the ice behind the front relentlessly pushes forward.

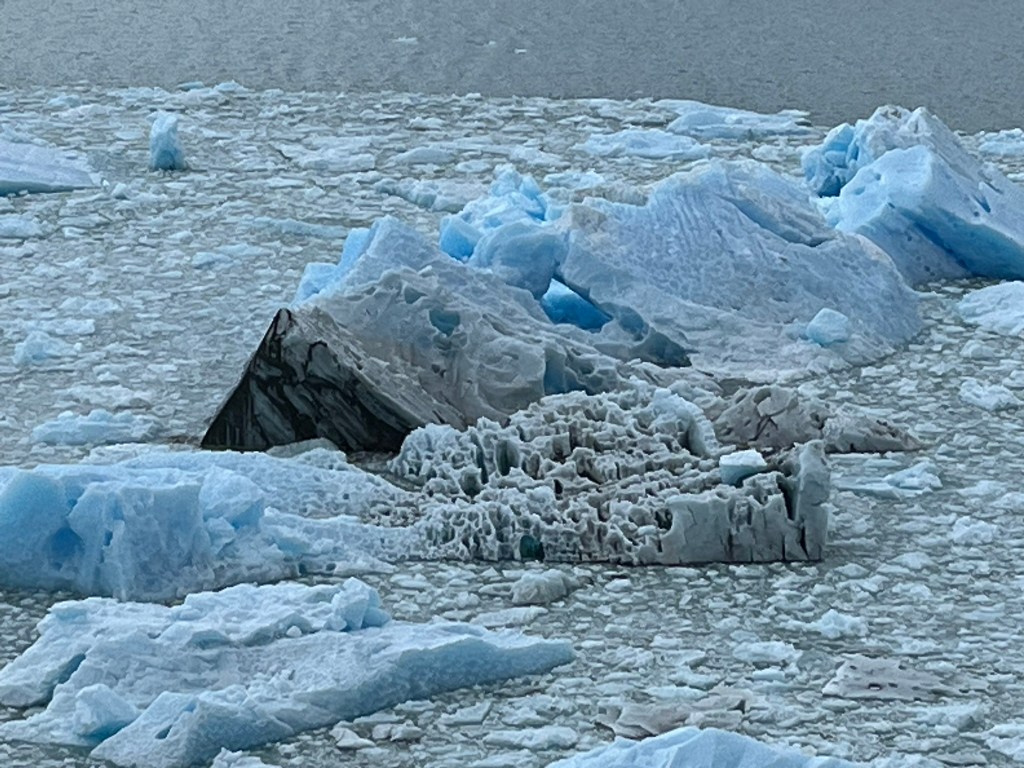

From the upper deck of the boat you get fantastic views across the glacier front and the huge icebergs that sit close by and must have calved recently. Getting this close to a glacier is a geographer’s dream.

The walkways, balconies and viewpoints are a 10-minute drive from the dock, built on the edge of Peninsula Magallenes and directly facing the glacier. There are a number of different walking circuits available that provide different angles of the glacier, but the Central Balcony is the absolute best. Here you get the classic postcard view of the entire glacier – both north and south faces and a view up to the accumulation zone further up the mountain behind the front.

Here you can see all the jagged ice peaks, and fantastic deep blue crevasses. We decided to stay here and watch and wait. We wanted to see a calving event and if we were walking around the various trails we might miss it. A few small blocks, maybe the size of a suitcase, although the size is really difficult to estimate, fell here and there along the front, making small splashes but nothing significant. And then suddenly, after a few small pieces of ice tumbled down part of the front, a whole big chunk collapsed into the water. The noise was incredible. And this wasn’t even that big a chunk, relatively speaking. If the visible wall height was 70m I would estimate what collapsed was about 20m in height and maybe 5m in depth. It submerged into the water quickly and waves rippled off into the distance.

What surprised me most how long the noise went on for, with all the other ice in the water disturbed from the new entrant. And how long the waves continued for. Eventually the newly formed iceberg found its balance, and just a small amount of what had crashed into the water was now visible. We were so lucky to see this and I can’t even begin to imagine what its like when truly huge pieces of the glacier calve into the water.

Perito Moreno Glacier is carved into metamorphic basement rocks, formed hundreds of millions of years ago. The valley it sits in is a steep U-shape, classic for glacial erosion. This valley was shaped during the last glacial maximum 12,000-20,000 years ago when Patagonia’s ice sheet was far larger and extended across much of the region. It is an outlet glacier of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field and is fed by heavy snowfall in the high Andes, internal ice flow moving downhill under its own weight (at roughly 2m per day) and tributary ice streams that help to thicken and stabilize the glacier.

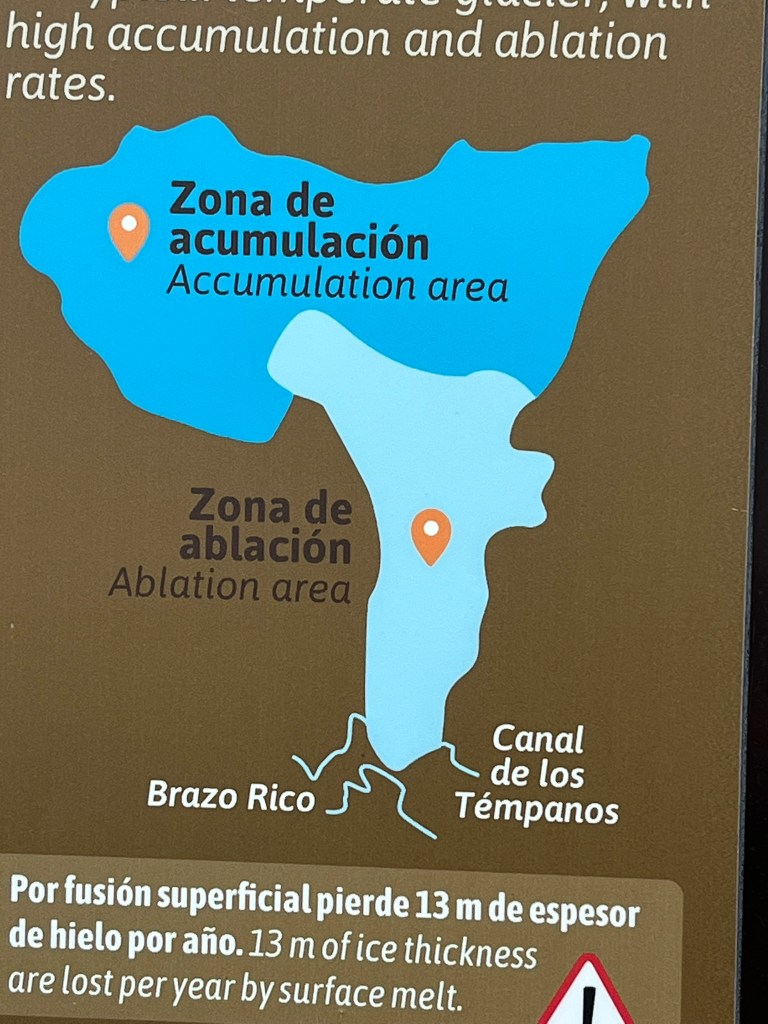

The glacier is unusual because it is not retreating overall, like many glaciers across the world have been observed to be. Whether it is advancing or retreating is determined by the balance between ice gained (snow fall + flow from above) and ice lost (melting + calving from the front). Most of the glacier front at Perito Moreno sits in shallow water and with no floating tongue, which slows calving and reduces flotation and rapid break up. This makes the front more resistant to retreat. At the same time the accumulation zone continues to receive high snowfall, which keeps the glacier well-supplied. The glacier is however always moving. It occasionally advances enough to form a natural ice dam and block the southern arm of the branch the glacier sits on. This is evidenced by the volume of dead trees that surround this part of the lake, caused by water rising in this area when the ice dam is present. Eventually the ice dam collapses in a spectacular rupture event. This cycle does not necessarily reflect climate conditions – it is controlled by the glacier’s geometry and lake depth.

This doesn’t mean climate change isn’t affecting the glacier. There are subtle signs that things are changing. Evidence shows that there is increasing meltwater in the Summer months, and pools of water develop on the surface during warm spells. Remote sensing has shown thinning in the accumulation zone – a sign that the long term balance may be shifting. And there are less predictable rupture cycles. The classic ‘every 4 years’ rupture pattern no longer holds, reflecting changes in water pressure, melt rates and flow speeds.

Recent studies have found that the glacier is now showing signs of retreat and mass loss. Since 2019 the glaciers front has receded up to 800m. And the thinning rate near the front has increased dramatically from 0.4 m/year (2000-2019) to 6.5m/year (2019-2024) in some places. For a glacier previously cited as a rare exception to the global trend of retreating glaciers, this development is noteworthy. It indicates that even the more resilient glaciers are now being impacted by climate-driven changes.

Another fantastic day here in Patagonia. The glaciers in Los Glaciares National Park do not disappoint. We are now on our way to our final stop in Patagonia – Ushuaia.

Leave a comment