Chile’s long, thin geography produced a mosaic of cultures, thousands of years before the Spanish conquest of the 16th century. It was never a unified civilization but rather a set of distinct cultural regions shaped by deserts, coasts, forests and mountains. Chile is one of the earliest known inhabited regions in the Americas. The archeological site in Monte Verde, near Puerto Montt, dates to ~14,500 years ago and shows evidence of nomadic hunter-gatherers who used simple stone tools, medicinal plans and huts made of wooden frames and animal hides.

Before the Spanish, Chile was not isolated and trade flowed across the Andes to Bolivia and Argentina, up the Pacific Coast and down the Central Valleys. These exchanges moved ideas, pottery styles, metals and food crops. In the early 1500s, the north was Inca-controlled and influenced, the central regions were semi-independent groups with mild Inca influence, and the south-central was independent Mapuche territory. There was no single ‘Chile’ but a chain of independent societies formed by climate zones.

In 1540 Pedro de Valdivia led a small expedition south from Cusco and founded Santiago del Nuevo Extremo in 1541 at the foot of Cerro Santa Lucia (the small hill near our hotel in Santiago). The choice of location was strategic, it was a defensible hill within a fertile valley and had access to to the Mapucho River. Almost immediately after it was founded the Mapuche and Picunche indigenous groups attacked and the Spanish only managed to survive due to indigenous allies and reinforcements arriving from Peru. Over the next decade, Valdivia established La Serena in the north and pushed south to the Bio-Bio River, founding several fort-towns along the way. Gold mining operations were launched near Valdivia and Concepcion.

The Arauco War broke out in the 1550s between the Mapuche people of south-central Chile and the Spanish Empire. It is one of the longest indigenous resistance wars in history and was on-going in waves until the 19th century. The war broke out because as the Spanish pushed south from Santiago in the 1540s they encountered the Mapuche heartland between the Itata and Tolten rivers. Valdivia was killed early on in the campaign, in 1553 at the Battle of Tucapel by Mapuche warriors led by their renowned leader Lautaro.

Although the Mapuche lacked central leadership and were political decentralised they were able to mobilise large forces and co-ordinate in war. The Spanish lost almost every settlement south of the Bio-Bio multiple times and in 1598 the Destruction of the Seven Cities wiped out Spanish presence from Valdivia all the way to to the island of Chiloe. Spain rebuilt Valdivia only because it was key to controlling possible Dutch incursions. By the mid-1600s both sides were exhausted and a frontier zone along the Bio-Bio river formed where trade, diplomacy and periodic warfare coexisted. The Mapuche were never conquered by the Spanish Empire.

During this time Chile became a Captaincy General, a remote frontier colony of the Viceroyalty of Peru. Chile stayed relatively poor but strategically important to Spain’s Pacific empire.

In 1810, local elites formed a junta when Napoleon invaded Spain and deposed King Ferdinand VII. Across Spanish America, local elites claimed they were defending the rights of the ‘legitimate king’ by governing themselves. However, Chile’s elites had long resented Lima’s control and wanted more autonomy. The early period of independence known as the ‘Patria Vieja’ was led by families like the Carreras and O’Higgins. A National Congress was created, political parties formed and efforts were made to form an army. The major issue was that independence forces were divided and royalists still held strongholds in southern Chile.

In 1814, Spanish royalist forces, supported from Lima, invaded central Chile and crushed the independents at the Battle of Rancagua. Independence temporarily collapsed and O’Higgins, the Carrera brothers and many other patriots fled across the Andes to Argentina. Chile was placed under harsh military law, but this increased support for full independence.

In 1817, from exile in Mendoza (Argentina), O’Higgins and Jose de San Martin (the Argentinian general) formed the Army of the Andes. Over 4000 men crossed six high mountain passes, with temperatures as low as -20, reaching central Chile and defeating the royalists at the Battle of Chacabuco, near Santiago. This effectively restored independence, but the fighting continued. O’Higgins was made Supreme Director and led the new Chilean state, focussing on building a navy, establishing education and new laws, and supporting San Martin’s larger liberation plan for Peru. The defining victory over the royalists in Chile came at the Battle of Maipu in 1818.

Chile built a navy under Lord Cochrane, a British admiral who became a national hero in South America. He cleared the Pacific coast of Spanish ships, enabling San Martin to invade Peru by sea in 1820. And captured key, previously impenetrable fortress-ports like Valdivia. The last royalist strongholds fell in Chiloe in 1826.

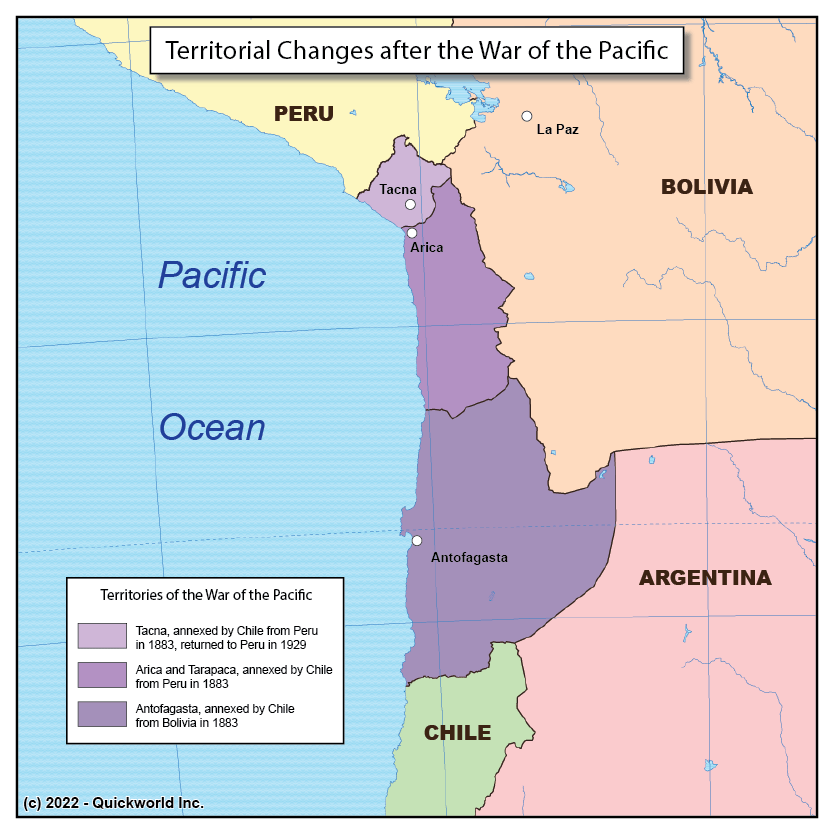

The War of the Pacific broke out in 1879 and was fought between Chile and an alliance of Peru and Bolivia. It reshaped the map of South America, with Chile expanding north, Peru losing major territory and Bolivia becoming landlocked. The conflict was primarily about nitrates, a mineral used for fertiliser but more importantly – explosives. The richest nitrate deposits were in the Atacama desert, specifically in the region between Chile, Bolivia and Southern Peru. But the borders here were badly defined.

Chilean companies were operating in Bolivian and Peruvian territory. Bolivia raised taxes on a major Chilean mining company, violating a treaty and then tried to seize the assests of the company. Chile responded by occupying the Bolivian port of Antofagasta. Bolivia declared war on Chile, and Peru was drawn into the war through a secret mutual defence pact between Peru and Bolivia. Initially the war was fought at sea and after a number of battles, Chile gained total naval control, allowing amphibious invasion of Peru. Chile overran forces in both Southern Peru and Bolivia and these became permanent Chilean territories after the war. For Chile, it gained vast nitrate-rich territories and became the wealthiest country on the Pacific coast for decades. For Peru it lost a major revenue source and remained economically weakened well into the 20th century. For Bolivia it lost access to the sea, and Chile and Bolivia continue even until today to have diplomatic tensions.

After winning the War of the Pacific, nitrates became 70-80% of Chile’s government revenue. British companies dominated the nitrate industry, and Iquique, Antofagasta and other desert towns became booming cities. Immigrant workers from Chile, Bolivia, Peru and Europe filled the desert pampas. From 1891 to 1925 Chile became a Parlimentary Republic and politics was dominated by Santiago’s elite. Harsh working conditions in the nitrate companies led to early worker movements including the Santa Maria de Iquique massacre in 1907 where the army killed hundreds of striking workers. By the 1920s, inequality and political paralysis was pushing the middle class and workers to rally behind new leaders. And then in 1929, nitrate prices collapsed permanently because of the invention of synthetic alternatives in Europe and Chile’s economy crashed.

From the 1930s to the 1950s, three consecutive presidents from the Radical Party came to power, creating many state-owned companies. In the 50s and 60s there was growing divisions between the right, center and left political parties. The country was deeply polarised.

In 1970 Salvador Allende was elected president, the world’s first democratically chosen Marxist leader. He launched the Unidad Popular program which nationalised copper production, forced rapid land reforms and expanded welfare and social spending. Polarisation exploded and strikes and protests surged. Inflation hit triple digits and food shortages grew. The US government opposed Allende who aligned with Cuba and the socialist bloc, and actively worked to destabilise his government. There was the fear that if Allende succeeded democratically in running a communist state then other Latin American countries might follow. This would undermine the US Cold War strategy globally. Nationalising copper also threatened US corporate power. Chile’s copper mines were largely controlled by 2 US companies, so controlling copper meant you could control the country.

On September 11 1973 a coup was held led by General Pinochet. Armed forces bombed the presidential palace and Allende died inside. By 1974 Pinochet became Chief of State in Chile, and established a military dictatorship. He dissolved congress and suspended the constitution. He banned political parties and imposed strict censorship and curfews. He ruled by decree for nearly 17 years, during which more than 3000 people were killed or disappeared, more than 28,000 tortured and over 200,000 exiled from Chile.

Pinochet invited the ‘Chicago Boys’ , Chilean economists trained at the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman, to redesign the economy and implement free-market reforms. Milton’s philosophy advocated neoliberal economics with free markets, limited government intervention, privatization and fiscal discipline. State-owned banks were sold to private investors. Price controls and trade barriers were removed. And there was tight control of inflation. Initially economic growth was seen, but in 1982 the Chilean economy suffered a severe recession due to overleveraging, external debt and a banking crisis. Many companies and banks collapsed and unemployment soared. By the mid-80s the economy had stabilised driven by exports of copper, forestry and agriculture.

In the long term, Chile became one of South America’s fastest growing economies. However, inequality increased, with wealth concentrated amongst the elites. And protests about the privatization of education, healthcare and pensions continued for decades. Economic growth came at the price of social inequality and political repression. The real-world implementation of neoliberal economic theory was a big experiment and has become a model studied in economics classes around the world.

At the Plebiscite of 1988, Pinochet called for a referendum to extend his rule. 55% voted No, forcing democratic elections. In 1990 Patricio Alwyn of the Christian Democratic Party became president and democracy officially returned to Chile. During his presidency prosecutions started for the human rights violations that had occurred during Pinochet’s regime, with high profile prosecutions of former military officers. By the mid-2000s Chile had become one of South America’s most stable and prosperous economies.

In the last 20 years Chile has experienced alternating center-right and center-left democratic governments. Despite strong economic growth and stability, social inequality persists, and culminated in country-wide protests in 2019 and 2020. Whilst we have been travelling in Chile, voters have gone to the polls in a general election. In the first round of voting, nobody got the required 50% so the vote is going to a second round. One candidate is far-left and one is far-right, with two very different visions for the future of Chile.

Leave a comment