My next destination is Patagonia. The end of the world. Or at least of South America. The word conjures up images in my mind of explorers, epic landscapes and emptiness. Everyone I have met who has been to this faraway place has raved about it but I have no idea what to expect! All I do know is that it will be a great adventure.

Patagonia spans the southernmost region of South America and is shared by Chile (western Patagonia) and Argentina (eastern Patagonia). It is over 1 million km^2 (bigger than France and Spain combined) but has a total population of just 2 million people. It’s pretty empty! Patagonia can also be roughly split into a north-south divide with the north dominated by forests, lakes and volcanoes and the south full of glaciers, granite towers and huge steppe. On this trip I will only be going to Southern Patagonia.

The region is a product of:

- The tectonic collision between the Nazca Plate and South American Plate, which created the Andes mountain range

- Volcanic activity, at the subduction zone between the two plates, building mountains and plateaus

- Glacial carving during the Ice Ages, shaping valleys, fjords, lakes and granite spires

- Wind and erosion on the eastern steppe, creating vast dry planes

Together these processes have created a distinct contrast between the wet, fjord-filled Chilean Patagonia and the dry wide-open Argentinian Patagonia. The Andes mountain range acts as a wall creating total climate separation between the east and west. Moisture arrives from the Pacific Ocean carried by strong westerly winds. When that moist Pacific air hits the Andes, it cools and drops a massive amount of rain on Western Patagonia. After releasing its moisture on the west side of the Andes, the air drops down the eastern side warm and dry. This creates a rain shadow, and is why Eastern Patagonia is so dry.

The east and west are also quite different geologically. On the western side, the Andes are still rising from tectonic collision. Volcanic activity and earthquakes are common. And landscapes include sharp granite towers like Torres del Pain and Fitz Roy, fjords from drowned glacial valley and the Southern Patagonian Ice Field. In the east the landscape is old, eroded and open. It was once part of the ancient Patagonian plateau, formed from basalt lava flows, sedimentary layers and fossil-rich badlands.

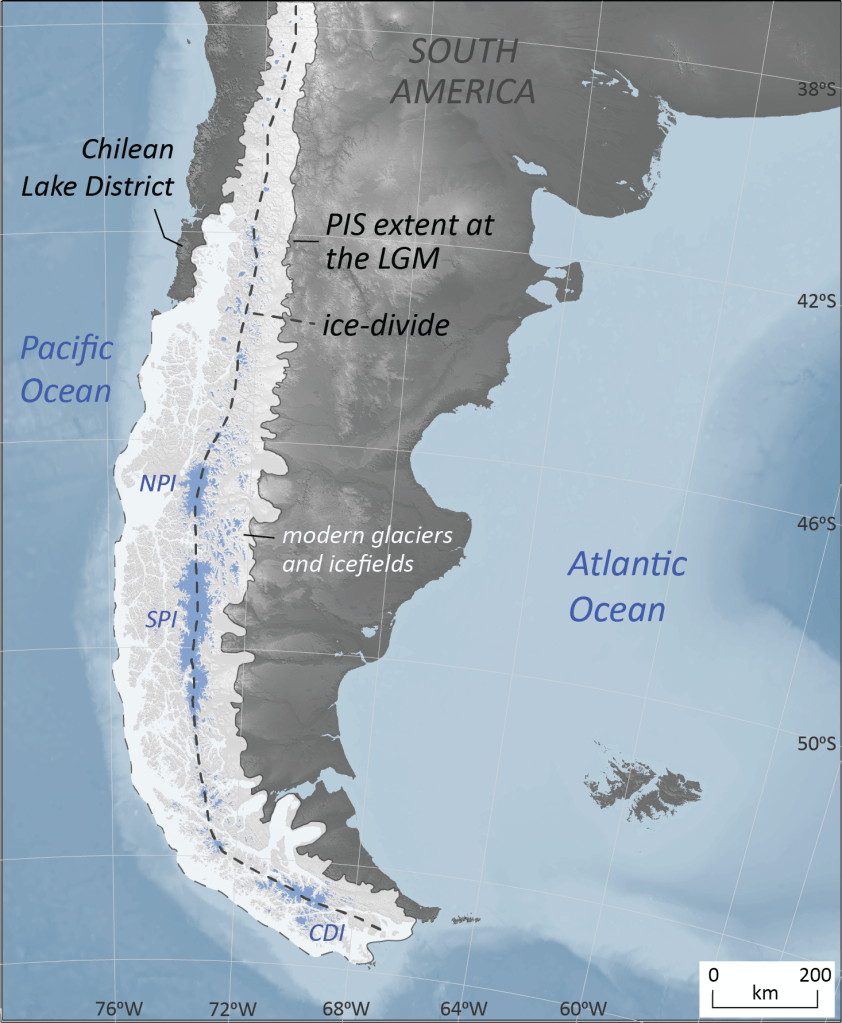

The Southern Patagonian Ice Field is the largest ice mass on Earth outside of Antarctica and Greenland. Most of the ice field sits in Chile, whilst many of the major glacier fronts sit in Argentina. It is a remnant of the enormmous Pleistocene ice sheets that once covered all of Patagonia during the last Ice Age (up to 20,000 years ago).

As Patagonia warmed, the ice retreated into the high Andes, leaving behind deeply carved valleys that formed fjords and lakes. The ice field persists today because of the unique combination of moist Pacific winds that strike the Andes and dump huge amounts of snow on the western side and the cold plateau climate that ensures that temperatures stay low at altitude. As long as accumulation at the top of the ice field roughly balances melting at the edges, the ice field will remain. The ice field feeds 48 major glaciers, three of which I will be visiting over the coming week.

The ice field explains almost everything about the landscape of Patagonia. The jagged peaks are the hard rock islands that poked above the ice sheet. The lakes are all glacially carved basins, and the color of the water comes from ‘rock flour’, fine sediment that has been ground up by the glaciers. And finally the wind – Patagonia’s fierce gusts come from the cold air pouring off the ice.

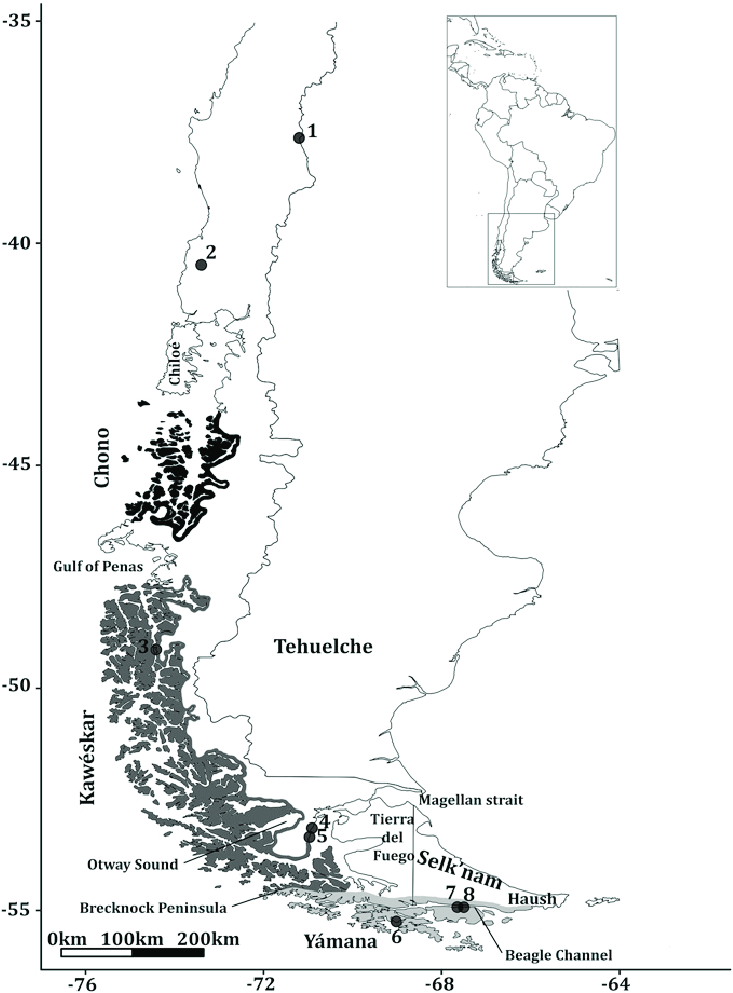

Patagonia was never the ’empty wilderness’ as early explorers imagined. For thousands of years, indigenous groups adapted to its extreme climates. There were 2 major cultural areas – the Steppe peoples of Argentina and the Canoe people of Chile and Tierra del Fuego.

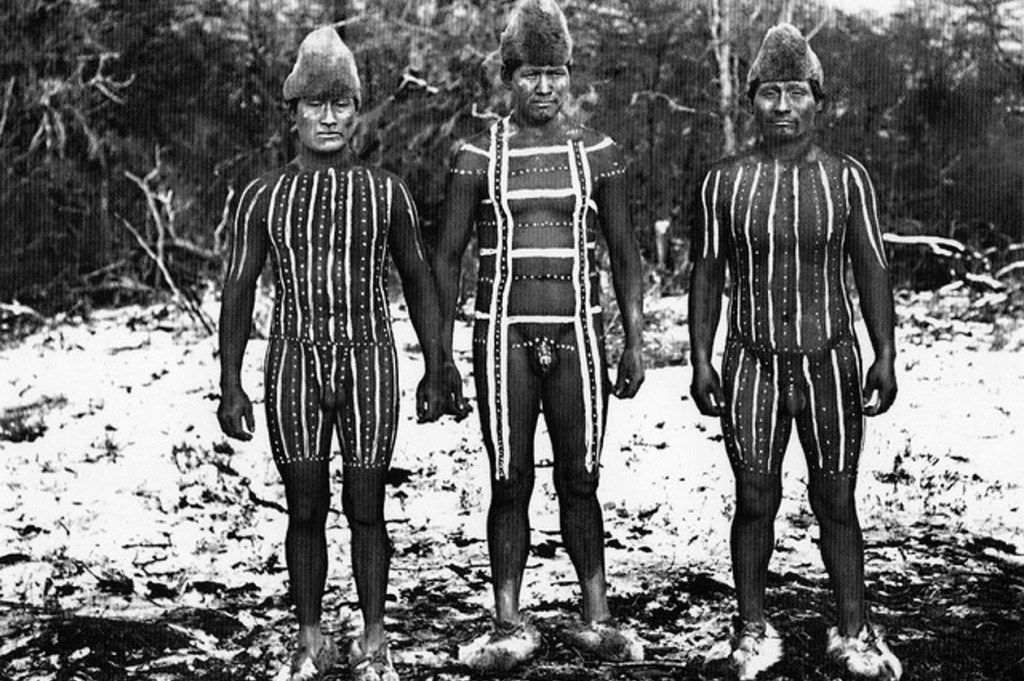

The Canoe People were groups called Yamana, Kawesqar and Selk’nam. They lived among the fjords, channels and islands of western Patagonia and moved around by canoe. The Selk’nam are especially known for their body-painting and minimal but effective clothing using grease and ash to protect against the cold.

The Selknam lived in relative isolation until the late 19th century when sheep-farming settlers arrived. The settlers saw the Selk’nam as a threat to ranching and bounty killings were organised with Selk’nam men, women and children being shot on sight. An estimated 4000 people were killed reducing the group to just a few dozen by the early 20th century.

The Steppe Peoples were groups called Tehuelche and Aonikenk. They were nomadic hunter-gatherers, who followed guanaco herds across the steppe in eastern Patagonia. Rock art like the Cueva de los Manos was created by these groups over 9000 years ago.

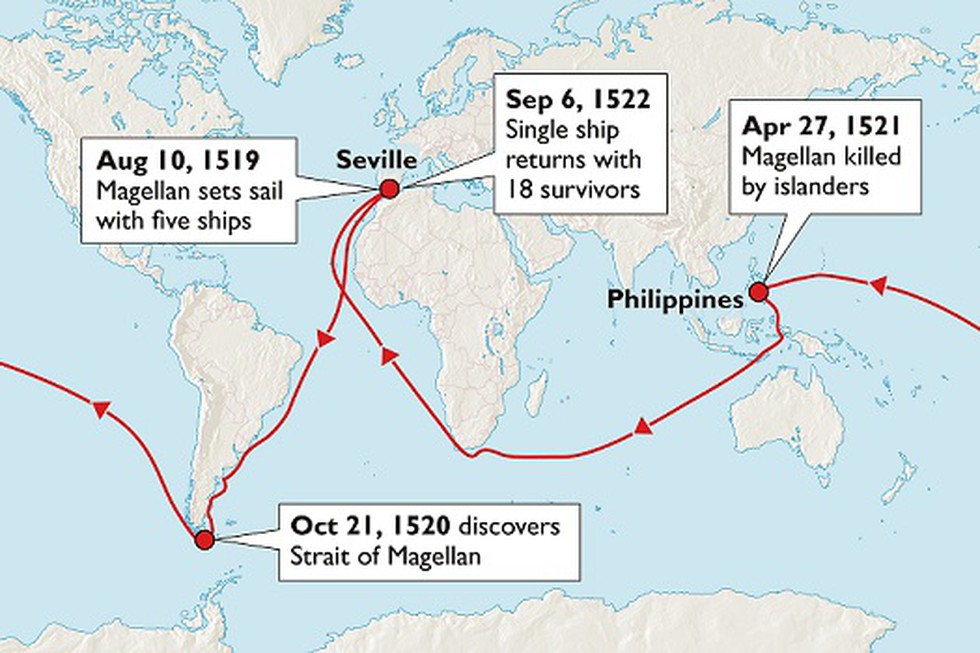

In 1520 Ferdinand Magellan arrived, sailing through what is now known as the Strait of Magellan, a navigable sea route that connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, avoiding the treacherous waters further south at Cape Horn. The name Patagonia came from a myth that this was the ‘land of giants’ after encounters with tall indigenous people. The Spanish word ‘patagon’ was used by Magellan to describe these people which literally translates as ‘big-footed people’.

Magellan claimed the land for Spain, and although there were a few follow up expeditions, none succeeded in establishing permanent settlements. The weather, isolation and lack of resources made it almost impossible. In fact, almost nothing happened for over 200 years and it was essentially ignored until the 1800s. Europeans would sail past it on their way to the Pacific side of South America, but not stay. Cartographers filled their maps of this region with mythical with giants and monsters. And the indigenous people continued to live largely undisturbed.

In the early 1800s, the British arrived. In the 1700s British whalers and seal hunters were among the first Europeans to spend long periods of time in southern Patagonia. They operated around the Falklands, the Beagle Channel and the coast of Tierra del Fuego. From 1826-1830 HMS Beagle mapped the Chilean fjords, the Strait of Magellan, Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia’s Atlantic coast. These maps were so accurate that modern charts still trace the outlines. In the Beagle’s second voyage from 1831-1836, Charles Darwin arrived in Patagonia, where he studied the geology, fossils and indigenous cultures. The crew documented glaciers, flora and fauna. All of this extensive mapping allowed safer sailing, and later, settlement. The Beagle expeditions put Patagonia firmly on the scientific map.

In 1843 Chile secured the strait as a strategic navigation route and Punta Arenas was founded becoming a penal colony and then a commercial port. This gave Chile a real foothold in southern Patagonia. Argentina’s government feared losing Patagonia to Chile, Britain or France. And by the 1870s Buenos Aires shifted from symbolic claims of the region to active expansion.

When sheep were introduced in the 1870s, this led to explosive economic change. British, Scottish, Croatian and Chilean entrepreneurs brought Merino sheep to the windswept grasslands. The steppe proved to be ideal with mild winters and vast open plains. Enormous ranched estates were created and huge fortunes were earnt by some families. The wool trade integrated Patagonia into global markets. The sheep boom eventually collapsed. The great depression in the 1930s devastated wool prices worldwide and many ranches became insolvent. Land prices crashed and thousands of workers lost their jobs. Then in the 1940s and onwards, competition from synthetic fibers meant that by the 1970s many ranches were unprofitable. The early 1990s brought the final blow, when global wool prices hit historic lows. Sheep ranching still exists in Patagonia but as a much smaller niche sector. Many historical ranches are now run for tourism and vast tracts of land have become national parks.

Now back to Chile and Argentina’s scuffles for territory. In 1878 Argentina’s Conquest of the Desert aimed at bringing Patagonia fully under state control and resulted in mass killings of the Tehuelche indigenous group. The Selk’nam in Tierra del Fuego met a similar fate. By 1900 Patagonia had shifted from indigenous lands to ranching territory controlled by states and immigrant families.

Gold was discovered in Tierra del Fuego and other areas in 1884. This brought more Europeans, Chileans and Argentinians to the region. The gold boom didn’t last but it intensified colonisation.

In 1881, Chile and Argentina agreed the Boundary Treaty where the Andes watershed line was used to split Patagonia between the two countries. And Tierra del Fuego was split with Chile taking the west and Argentina the east. But the exact details of the border were unclear. After nearly going to war, in 1902, after arbitration run by the British, most fjord regions were awarded to Chile and the eastern slopes to Argentina. The countries nearly went to war a second time in the 1970s over islands near Cape Horn. This was eventually resolved by papal mediation in 1984, stabilising the region.

Today, tourism is the main economy of the region. There are also large-scale conservation projects underway across the region. National parks are being expanded and fjords and forests that were previously only for logging and ranching are now being protected. And there has been a revival of indigenous cultures.

During my time in Patagonia I will be visiting Punta Arenas, Torres del Paine, El Calafate and Ushuaia.

Leave a comment