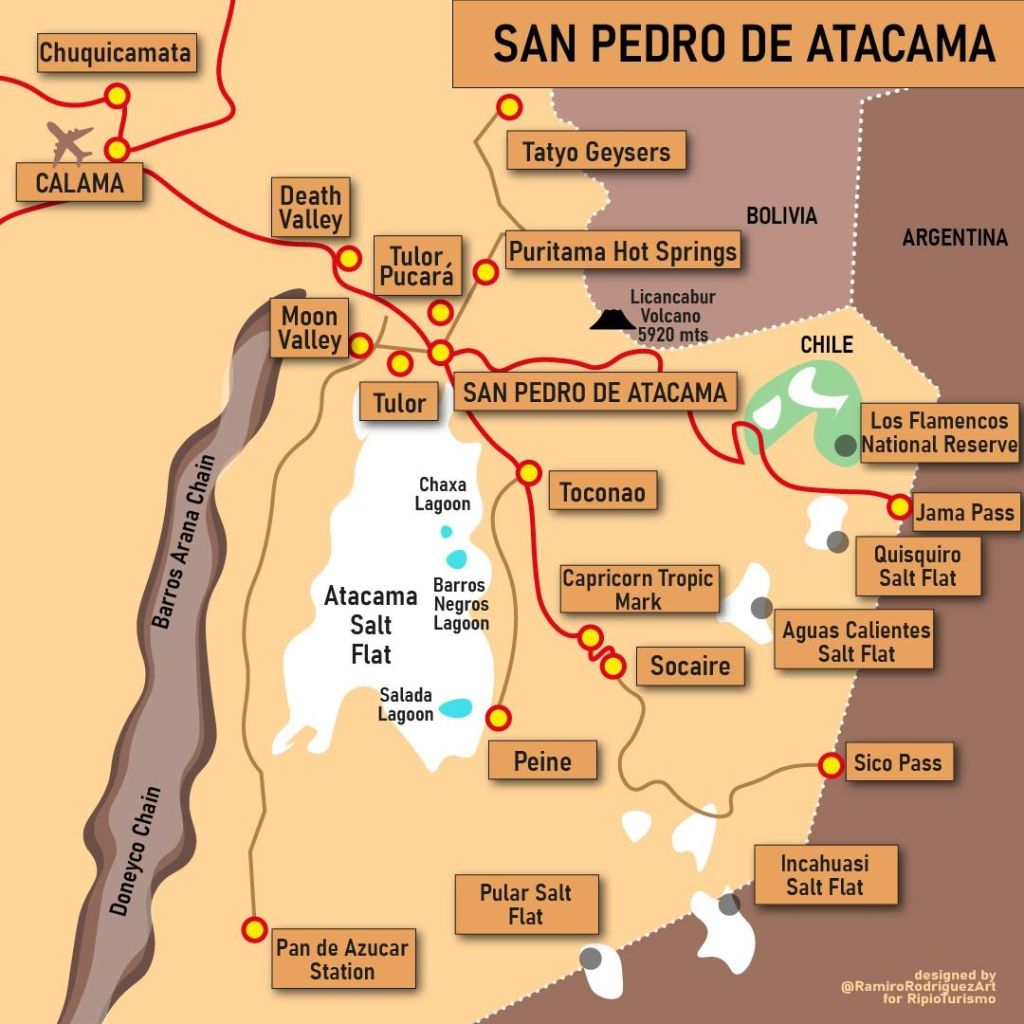

Moon Valley lies 13km west of San Pedro de Atacama inside the Salt Mountain Range (Cordillera de la Sal), running north-south along the western edge of the Atacama Salt Flat (Salar de Atacama). Parts of this valley have not received rainfall for centuries and there is almost no vegetation.

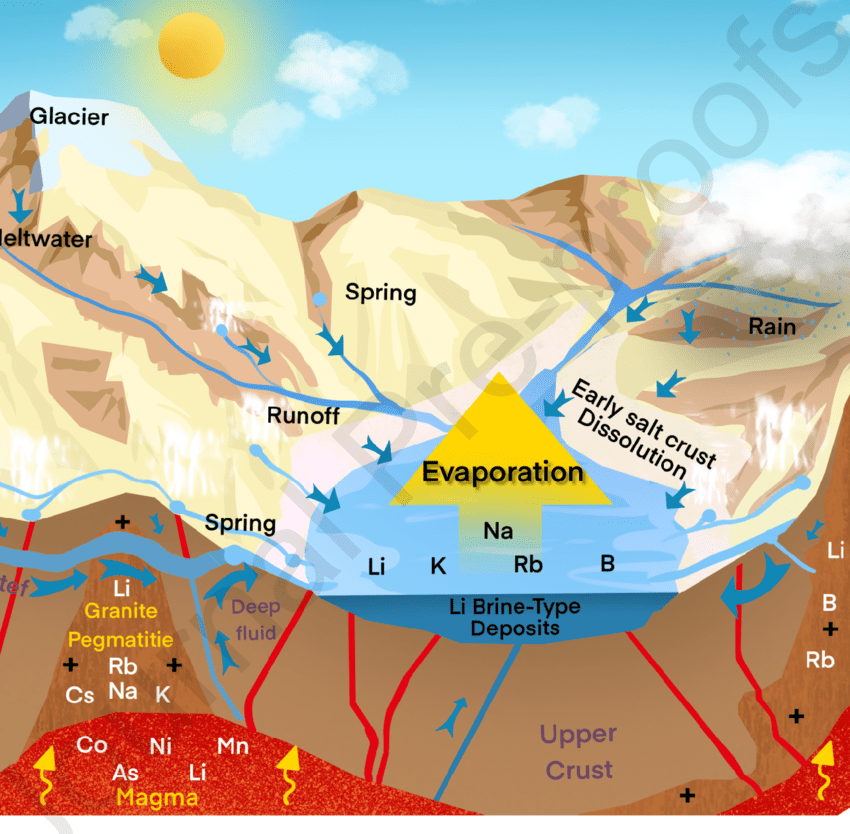

The Cordillera de la Sal is is formed from evaporites (salt, gypsum, halite), sedimentary layers (clays, muds, sandstones) and volcanic ash layers from ancient Andean eruptions. 20-25 million years ago this area was a large inland basin, periodically filled with lakes. During this time layers of clay, sand, and huge volumes of salt accumulated as lake water evaporated. Tectonic compression from the rising Andes folded and uplifted these layers, folding the salt like clay. Then over millions of years, wind and some water erosion exposed the sharp ridges, narrow canyons and fields of cracked salt polygons that can be seen today. The valley looks so much like the moon that NASA tests its Mars rover equipment here.

The geological features here are otherworldly and spectacular. We started our afternoon trip to the valley by walking up to the top of the Great Dune, through a winding narrow path where we could get up close to the cliffs and broken rock walls streaked with thin white veins. These white mineral veins are made up of Gypsum (calcium sulfate), Calcite (calcium carbonate) and halite (salt). You can also see thin sheets of gypsum that literally looks like it is pealing off the side of the rocks. Even the ground itself that you are walking on is covered with white crunchy salt and gypsum.

The path up to the top of the dune takes about 25 minutes with just the last couple of minutes requiring you to walk through softer, deeper sand and with no shade. But the view from the top is totally worth it. Directly beneath you sits the salt mountain range with its jagged knife-edge ridges and deeply folded layers of rock. In the distance a enormous curved wall of rocks with thick, distinct sedimentary layers sits. This is known as the ‘amphitheatre’. And if you turn around you gets an iconic postcard view of the Andes and the perfectly conical Volcano Licancabur. This place is a geographer’s dream. And looks like a movie set.

As we continued along the valley, after our dune climb, we stopped in a place called Las Tres Marias, named after a group of three eroded salt-clay-gypsum pillars that are said to resemble three biblical figures kneeling in prayers. More interesting though is the evaporite crust that covers every part of the valley floor. Evaporites are minerals that form when salty water evaporates completely. Up close you’ll see shards of translucent salt, crunchy popcorn-like gypsum nodules and salt filaments pushing up and forming ridges. It is all broken up because it is constantly expanding, shrinking and being pushed upwards because the salt and gypsum are extremely sensitive to tiny changes in humidity, temperature and moisture trapped underground. Even in the Atacama there is enough overnight humidity for the crystals to absorb that tiny bit of moisture, expand, dry in the sun and contract. It creates a stunning effect on the ground.

Moon Valley was historically mined for evaporate minerals. Gypsum was used in plaster, cement, construction and soil conditioners. It is extremely abundant in the folded ridges of the mountain range and was one of the main resources extracted. Salt was mined to use as both common and industrial salt. And nitrates were extracted for fertilizer and explosives.

We visited what was left of a small mining operation nearby the great dune where we could still see old cuttings in the rock walls, shallow pits where salt slabs were removed and old generators. The mining here declined by the 70s, as tourism interest grew and the Chilean government realised the area’s geological value and the damage the mining was causing. In 1982, Valle de la Luna became part of Los Flamencos National Reserve and conservation of the area took priority. The area is managed extremely carefully and you can only walk on dedicated paths in the reserve to stop the fragile valley floor from being damaged.

To end our first afternoon in the Atacama we headed up to the Kari Viewpoint, a rock promontory on the western edge of the Cordillera de la Sal that is a great place to watch the sunset and watch the changing colors of the Atacama desert at the end of the day. As we drove up to the view point, the road took us through a series of ragged, folded mountains called ‘Dinosaur Gorge’. Its nothing to do with real dinosaurs, instead the nickname comes from the tall, eroded clay-and-salt walls and jagged ridges that look like the spines, plates and tails of a stegosaurus.

A great first afternoon in the Atacama and we have lots planned for the coming days!

Leave a comment