Easter Island. Rapanui. Isla de Pascua. The island with the mysterious moai statues.

This lone volcanic island, just 164km^2 in the Southeast Pacific Ocean is one of the most isolated places on the planet. It is over 2000 km from the next inhabited island, the Pitcairn’s, and over 3000km west of Chile. Just two flights arrive and depart a day on the island during peak tourist season, both flying in from Santiago, Chile. The flight time is just under 5 hours and the entire flight is over the Pacific Ocean. This place is so far away from the rest of the islands in the Pacific, that just 14 cruise ships a year choose to include it in their itinerary. So why have we left mainland Chile and headed into the Pacific Ocean for 4 days of our trip?

It is estimated that the first settlements on the island were Polynesian voyagers sometime in the 13th century. Oral traditions names the founding chief as Hotu Matu’a arriving from Hiva (a place linked with the Marquesas islands) and landing at Anakena beach. DNA research, linguistics and archeological findings all support the theory of Polynesian origin. After settling the island, land was divided among clans. These clans ringed the coast with ceremonial platforms and raised enormous moai statues that represented ancestral chiefs facing inward towards the clan villages. It is estimated that there are around 900 moai statues and 300 ceremonial platforms across this tiny island. A huge amount of mystery, still even today, surrounds the statues, the people who built them and why they stopped.

Today, Rapanui is an island with around 5000 residents. The main (and only) town is Hanga Roa and the economy is predominantly tourism. It is a special territory of Chile and forms part of the Valparaiso region, 3000km away. Our flight arrived in the early afternoon and we were greeted at the airport with traditional local music and dancing. For many travellers, coming here is a bucket list trip and you could sense the excitement as people took photos of the plane and airport as we celebrated arriving.

We were met with flower garlands and jumped in the mini-bus that would transfer us to our hotel. Hanga Roa is a small town, and you can walk across it from end to the other probably in 15 minutes, so it was funny to watch folks on the bus be dropped off 50m down the road from the airport. It would have been quicker for them to walk! Our hotel, Hare Nua, was in a great location, right on one of the main roads heading to the central square of the town, and beautifully decorated. With around just 20 rooms, the personalised service was incredible. I would definitely recommend staying here on a trip to the island.

The rest of today was free for us to explore, but with 2 full-day tours booked for the upcoming days we wandered down to the coast line, had a bite to eat and called it a day. To visit the majority of the sites on the island you need to purchase a National Park entry ticket at $100 USD and you may only visit the sites on a guided tour. The Rapa Nui National Park was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995 and the park fees go towards providing all the services the park needs to operate.

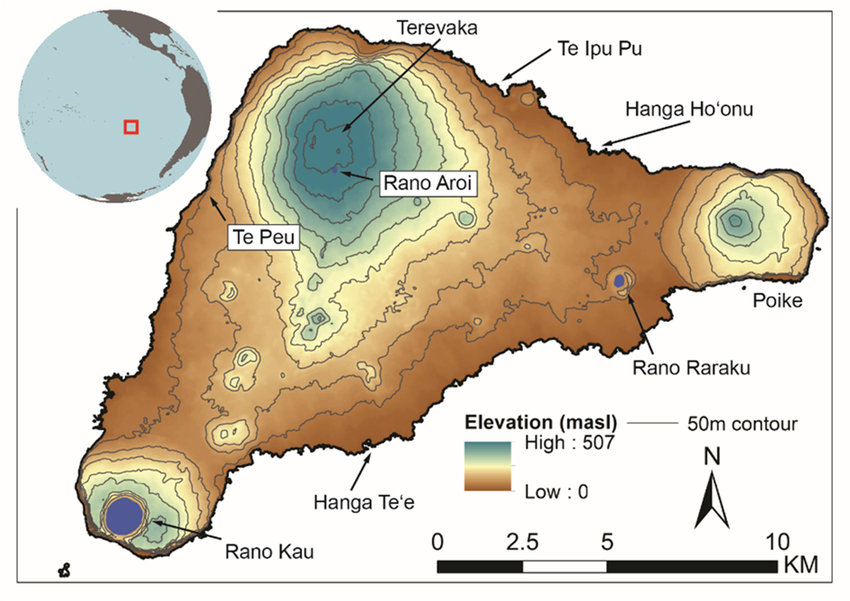

The island consists of three coalesced, now-extinct, shield volcanoes that erupted at the Easter hotspot between 3 million and 300,000 years ago. Terevaka is the youngest of the three, dominating the north and center of the island. Poike forms the eastern headland. And Ranu Kau is the oldest, forming the southern headland. The island is tiny and from the top of Rano Kau you can easily see the entire island.

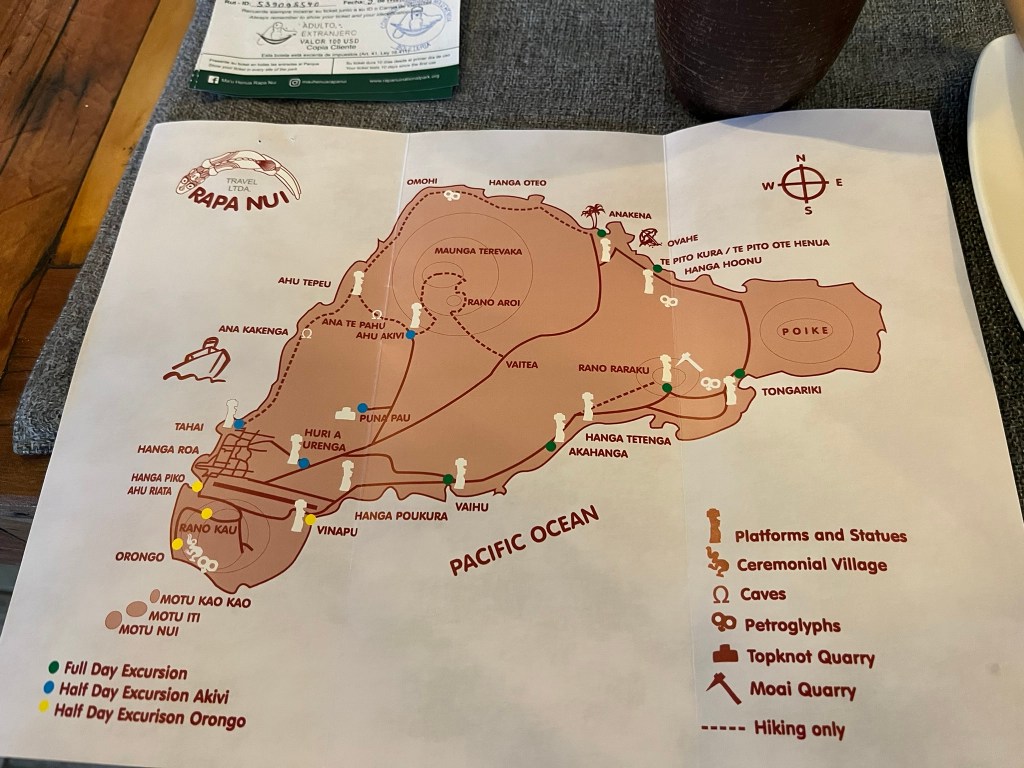

On our first day we visited the archeological sites of Ahu Akahanga, Ahu Hanga Te’e, Ahu Tongariki, Rano Raraku (the quarry), Ahu Te Pito Kura, finally ending at Anakena. At the first 2 sites, our guide explained how the villages were laid out, with chicken coops, gardens and house foundations all made out of the abundant volcanic rock of the island. Holes were carved into brick-shape rocks so that palm fronds could be bent over to make narrow boat-shaped houses. The gardens were built with high walls, to create small micro-climates where sweet potato, taro and banana could easily grow and be protected from the harsh and salty winds coming off the ocean. And the chicken coops were windowless structures with secret entrances for the chickens to go in and out of, protecting them at night and from stealing from rival clans.

Each village was typically near a lava tube cave, a place where refuge could be sought when pirates arrived on the island and where many families ended up living when resources had depleted beyond repair and there were no more palm fronds to cover their houses. Our guide, a native of Rapa Nui shared that his grandmother lived in a cave when she was two years old, demonstrating that this part of the island’s history was not so long ago.

Our first sight of a fallen moai statue was at Ahu Hanga Te’e. The statue was face down, facing inwards to the island, with the fantastic backdrop of the volcanic coast. This is how all the moai were positioned until about 70 years ago when attempts began to re-erect some of these enormous statues back onto their ceremonial platforms. Mystery continues to surround, how such heavy and tall structures were carried from the quarry of the island to the clan villages, how they were erected, what their purpose was and why they were torn down. The prevailing theory in why they were all torn down is that clans began competing with each other, creating bigger and bigger statues to represent their ancestors. The guide described it as an obsession that took precedence over everything else.

The manpower required to construct and move these statues, over time, used up a huge amount of resource and depleted the food available for people within the clans. This is thought to have started a civil war between clans, and tearing down a clans monuments to their ancestors weakened the morale of a village. There are lots of theories about what might have happened, so I’m not sharing what I know happened, rather what the guide shared with us. Some opposing arguments say that none of the bodies on the island have been found with wounds from weapons, which suggests no civil war.

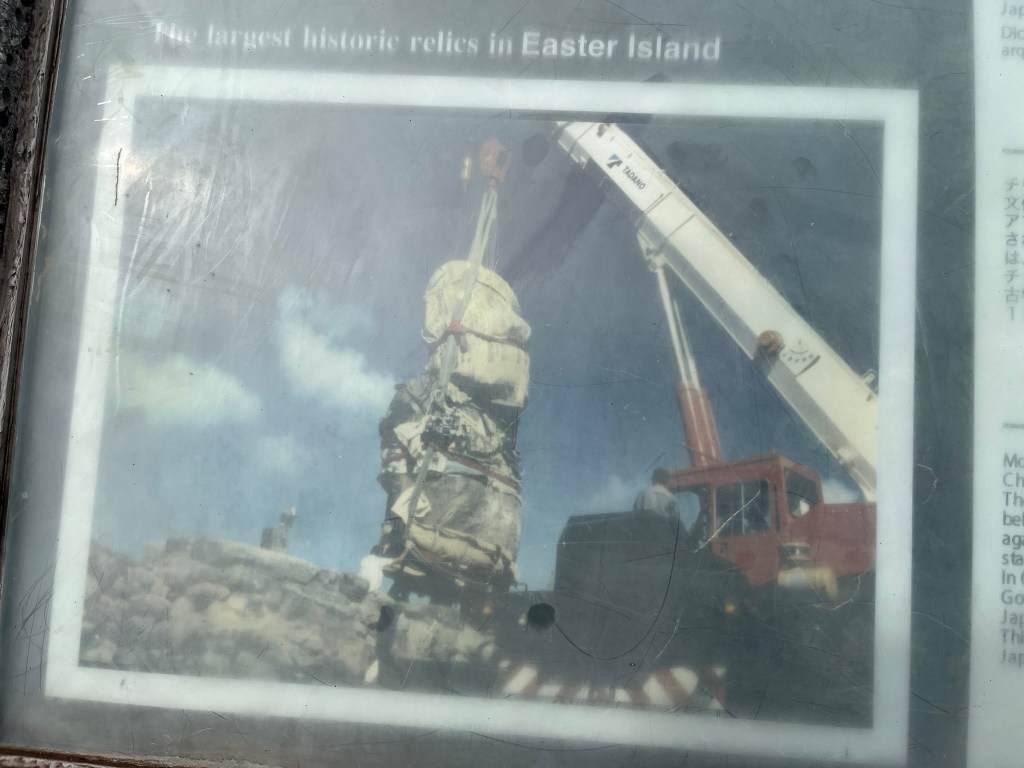

Our first ‘wow’ moment came at Ahu Tongariki. Here there is a line of 15 restored moai, some still with their red top knots in place, on a long ceremonial platform, and a spectacular backdrop of waves crashing into the steep volcanic cliffs of the island. The restoration was completed by a Japanese-Chilean team in the 1990s. This is easily one of the highlights of the island and a must-see sight.

Just behind Ahu Tongariki lies the quarry from which all the statues on the island were made and transported from. Today, there are hundreds of unfinished statues all in various stages of completion. There are standing statues at various angles, secured deeply in the soil and still positioned as they have been for over 100 years. There are half-carved statues, not yet separated from the quarry. And there are broken statues, spread across the landscape, presumably dropped and broken on their way to a clan village and abandoned. The big question at this site is why did the islanders suddenly stop creating the statues? Its clear that it was abrupt, from the half-finished state of the hundreds of moai at this location. It is like the artisans who carved the statues just disappeared one day.

We know what was left behind represents the end of the moai era, since they are some of the biggest on the island. Smaller statues represent moai that were carved in the early period, before the obsession with building bigger and bigger began. The largest unfinished moai in the quarry is 21.6m tall and would have weighed over 100 tonnes. How did the clans transport these gigantic monoliths without modern technology? The Japanese had to bring in a crane to restore the Tongariki moai! The walk around the quarry takes about 1 hour at a slow pace, and you get to see the statues really up close. Another must-see sight on the island.

After a lunch pitstop we headed to Ahu Te Pito Kura. Here you can see the now toppled, tallest moai erected, standing at just under 10m. Alongside the statue is the ‘navel of the world stone’. This nearly-spherical basaltic boulder, is about 80cm in diameter, and extremely smooth and polished. Around it are 4 smaller stones, forming a simple compass-like arrangement. According to Rapanui oral tradition, the sacred stone was brought by Hotu Matu’a, the island’s founding king, from his homeland of Hiva in the canoe that brought the first settlers. It was said to contain a spiritual power. Modern folklore says that the stone emits a strong magnetic energy and that compasses or watches go haywire when nearby. However, scientific checks have shown no significant magnetism, beyond that naturally within basalt.

From here we travelled to our last sight today – Anakena. Here just behind the white-coral sand beach lie 2 archaeological sights and it is thought this was a royal site and where the chief of the island resided. The principal ceremonial platform of Ahu Nau Nau was restored in the late 80s, with 7 moai, of which 4 have the fantastic red scoria topknots, that are not hats as many assume, but representations of hair wrapped into a bun. The hair of the local people was not red, but it was painted that color using the red soil of the land for ceremonial purposes. The top knots or ‘pukao’ were made at a separate quarry to the statues, called Puna Pau, a small crater east of Hanga Roa, which we are visiting tomorrow. The red scoria found in this quarry is a porous volcanic rock heavy in iron, lighter than the volcanic tuff used for the bodies of the statues, but still weighing up to 12 tonnes, for cylinders 2-3m wide. The top knots are seen in the later period of moai construction, and could be attributed to the clans wanting to make their statues bigger and better than other clans. We don’t know.

The Ahu Nau Nau statues are extremely well-preserved because they were found partially buried in the sand. This means we could more clearly see some of the delicate details that have since eroded on more exposed statues elsewhere. You can clearly see the ear ornaments, belt motifs and back tattoos. I liked these moai, as they looked more like real people than some of the bigger statues we had seen earlier in the day.

A smaller Ahu sits just behind the ceremonial platform. This was the first statue to be restored on the island, when in 1956 a team experimented with re-erecting the moai using only wooden levers, stones and ropes to test out Polynesian engineering methods.

Our first day of exploring this tiny island in the middle of the Pacific was absolutely fantastic. Truly a bucket-list place to come and the moai are as stunning in-person as they look in the pictures. I can’t wait to go out tomorrow and see more of the island.

Leave a comment