After a long 7+ hour train ride from Zhangjiajie to Guilin and a delay in getting picked up by the guide, who some how went to the wrong train station to pick me up, we jumped straight into sightseeing in Guilin City. Something that has come up quite a few times on this trip has been the impact across China from the war with Japan, particularly related to cultural buildings that were destroyed. So I thought I had better do some research into the first and second Sino-Japanese wars to understand which parts of China were affected, what happened and why.

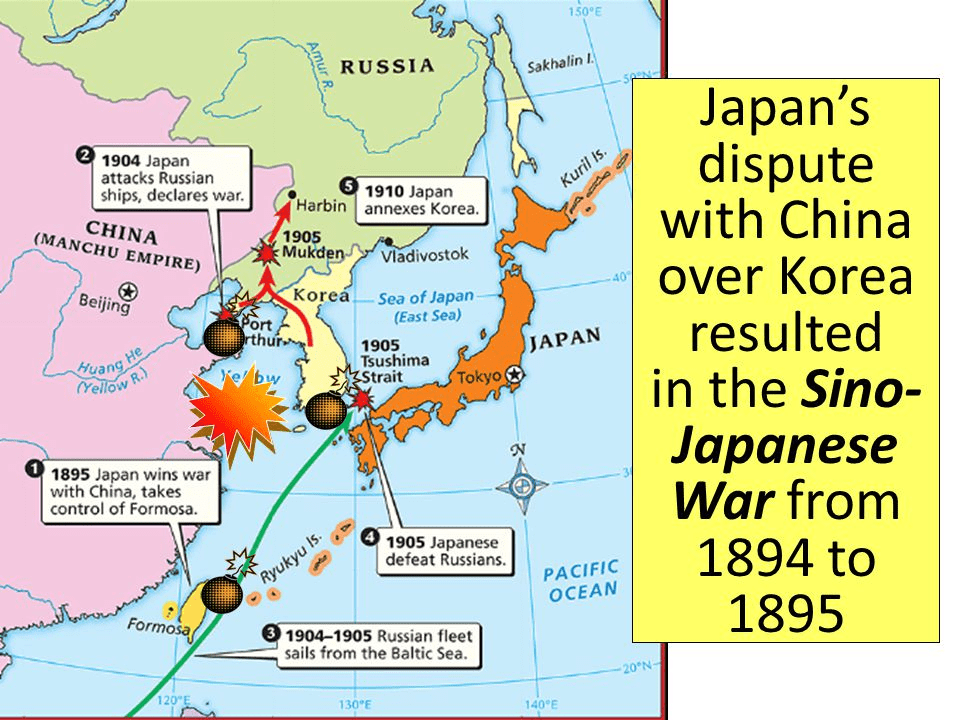

The First Sino-Japanese War occurred from 1894-95 and was the first major modern conflict between China and Japan. By the late 19th century both China and Japan were claiming influence over Korea, which back then was a tributary state of the Qing dynasty but increasingly seeking independence. Japan was newly industrialised and militarised and wanted to expand its sphere of influence. It saw Korea as strategically vital.

In 1894, there was a Korean peasant rebellion known as the Donghak uprising, which prompted both powers to send troops. Negotiations failed and fighting broke out. Initial clashes took place in the Korean cities of Asan and Pyongyang. The Japanese forces defeated Chinese forces and quickly took control of Korea, pushing Qing dynasty troops north into Manchuria. After this, Korea was effectively independent, but under strong Japanese influence.

Japan invaded Manchuria in the northeast of China and captured a number of cities, including Dalian, then known as Port Arthur. China’s modern navy was based in Dalian and the Japanese sank many Chinese ships during naval battles in the Yellow Sea and Bohai Gulf. This neutralized China’s naval strength.

Next Japanese troops invaded Taiwan, which was then also Qing dynasty territory. China’s defeat forced the Qing government to sign a humiliating treaty. The treaty recognised Korea’s independence and ceded Taiwan to Japan. It had a massive indemnity payment and was forced to open more treaty ports to Japan for trading. The war shattered the prestige of the Qing dynasty and Japan emerged as a modern imperial power. Japan gained international recognition and this resulted in the country having the confidence to challenge Russia a decade later during the Russo-Japanese War from 1904-05. The loss spurred Chinese reform movements.

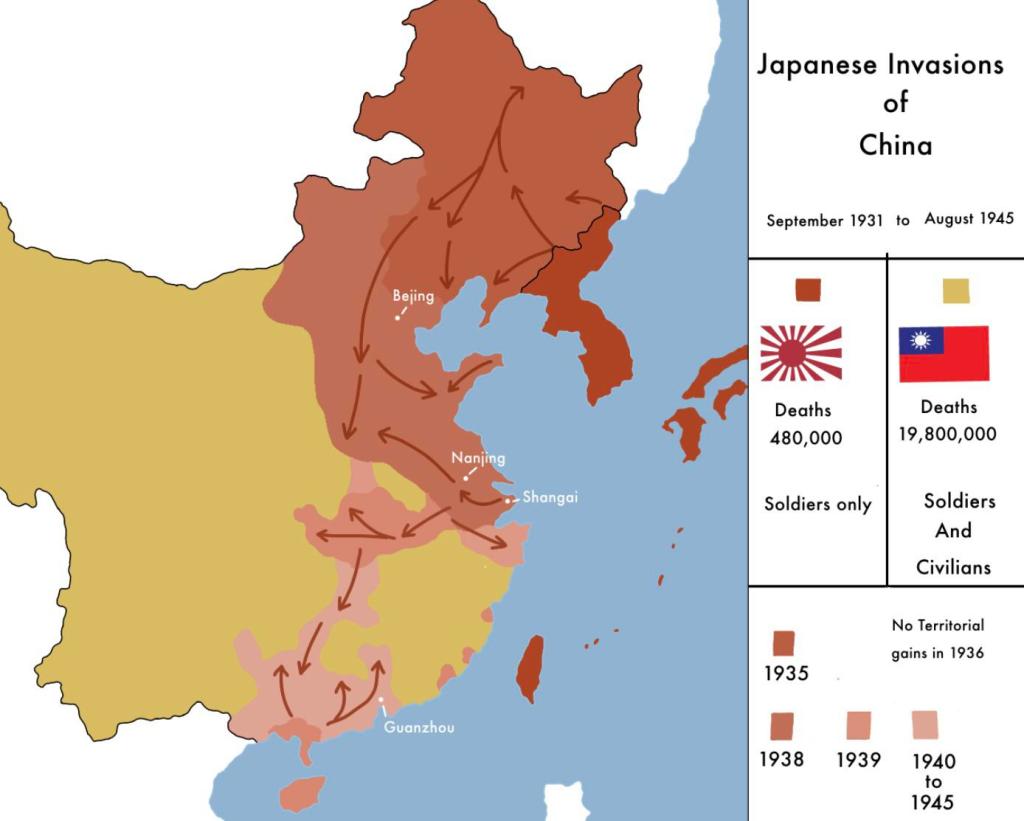

The Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937 and lasted until 1945. In the interim period, Japan had doubled down on its efforts to expand. It defeated Russia in 1905 and took Manchuria after 1931. Their foothold in Manchuria eventually became a springboard for a full invasion of China in 1937. Following the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, China was fragmented between warlords until Chiang-Kai-shek’s Nationalist government began reunification in the late 1920s. Japan viewed a stronger and more unified China as a threat to its economic and strategic interests.

The first conflict between these two nations was a limited war over control for Korea. The second was a total war, with aerial bombardments, civilian massacres and scorched-earth tactics. It formed part of Japan’s wider plan to build a ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere’ and their earlier success convinced them that China could always be defeated.

In 1931, Japan staged a railway explosion near Shenyang as a pretext to invade Manchuria, creating the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932. Over the next few years Japan expanded its influence in north China. The Marco Polo Bridge incident in 1937 was the trigger for all out war. A squirmish in a town outside Beijing over a missing soldier resulted in shots being fired and within days local fighting had spread to Tianjin, Beijing and across northern China. Both sides refused to back down because of national pride and an unwillingness to be humiliated. The League of Nations was powerless to intervene and Western powers were distracted by the war in Europe. At this stage it was simply a bilateral war between two countries.

Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei fell early in the campaign and Japanese forces pushed into Shanxi and Inner Mongolia. Later that year Shangai was captured after brutal urban fighting in the city. The Japanese then advanced up the Yangtze River to Nanjing which fell near the end of 1937. The Nanjing Massacre followed, where tens of thousands of civilians and prisoners were murdered.

Japan then moved into the industrial and agricultural heartlands; Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Hubei, Henan and Hunan provinces. Key cities in these regions were repeatedly bombed and fought over. Fighting spread south towards Guangdong, Guanxi (where I am currently writing this) and Hainan Island. Hong Kong was seized by late 1941.

Japan was already part of the Axis bloc with Germany and Italy through the Tripartite Pact, signed in 1940, but the war in China remained officially separate. However the fronts became increasingly connected. China was receiving Allied aid via the Burma Road from British India through to Yunnan. And the US was supplying weapons. Japan’s occupation of China put it in direct conflict with Allied economic interests in Asia.

In response to the increasing reports of atrocities being committed by the Japanese army, Western countries imposed economic sanctions, freezing Japanese assets and imposing a total oil embargo which cut off 80% of its supply. Japan’s leaders weighed up 3 options, withdraw from China and restore trade, continue fighting and hope for negotiation. Or seize resource-rich colonies in Southeast Asia. It went with the third option. But these colonies were under Western influence and Japan knew that invading them would provoke war with US and Britain. Japan’s military planners concluded that if war with the West was unavoidable then they must strike first, crippling the US Pacific Fleet before it could intervene. The result – the Pearl Harbor attack. At the same time Japan attacked Hong Kong, Malaya, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies. And the next day the US and Britain declared war on Japan. In return, Germany and Italy declared war on the US under the Tripartite agreement, merging the Asian and European conflicts into a single global war.

Now back to what was happening in China. By 1942 the nationalist government had relocated to Chongqing, which became China’s wartime capital and suffered relentless bombing. However, Japan’s army in China was trapped in an enormous unwinnable campaign. It was bleeding itself dry in China whilst also fighting the US and its allies across the Pacific and Southeast Asia. By 1944-45, many Japanese troops in China were isolated and starving, unable even to retreat effectively. Two events sealed Japan’s fate and forced it to withdraw from China. Firstly, the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And secondly, the Soviet invasion of Manchuria. On 15th August 1945, Japan surrendered and under Allied occupation terms had to evacuate all troops from conflict zones.

The aftermath and legacy of the Second Sino-Japanese War was profound. It is the single most devastating event in modern Chinese history and completely reshaped both China’s future and the balance of power in Asia. It is estimated that 15-20 million Chinese civilians died and ten of millions were displaced during the war. Entire cities were bombed and destroyed, and infrastructure, farmland and industry across the Yangtze basin and northern plains lay in ruins. Many regions were suffering from famine and epidemics. Following Japan’s defeat, control of Chinese territory was restored to the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek, although this was contested shortly after by the Mao’s Communist Part, leading directly to the Chinese Civil War of 1946-49. However that’s for another blog, another day.

The country was economically shattered, politically divided and dependent on foreign aid. The war has fostered a long-term deep suspicion of foreign interference and shaped policies of self-reliance that continue even today. A ‘never again’ theme is prevalent across many of the economic and political decisions the country makes. China’s rapid military expansion today, especially its navy is very much deeply rooted in the legacy of the Second Sino-Japanese War. China’s official narrative of the ‘Century of Humiliation’ – a period beginning with the Opium Wars and ending with Japanese surrender, is that China was invaded repeatedly by foreign powers, fragmented and occupied, largely because it could not defend itself. And so modern Chinese leaders continue to push the narrative that China ‘must have a strong military for a strong nation’, sending a message that never again will China be bullied or invaded.

For me personally, I think this part of China’s history explains a lot of why China is like it is today, and why it often takes an aggressive stance towards foreign influence of any sort. Its been caught out once and it won’t let it happen again.

Leave a comment