As I am stuck in Kathmandu because of high-intensity monsoon rainfall I thought it was the perfect time to write about the weather of Nepal, particularly the monsoon rains and how climate-patterns in the country are rapidly shifting. Currently, it has been forecast that the entire country will experience intense rainfall for the next 3 days. No travel in and out of Kathmandu valley via the highways is currently allowed, to try and manage landslide risk. And almost all domestic flights have been cancelled. A similar weather event happened last October and claimed 250 lives, so this year the government is taking extra safety precautions and is also more prepared to deal with the aftermath, with bulldozers and helicopters on standby to clear roads and make rescues respectively.

Nepal’s weather varies dramatically across both season and altitude, but the monsoon defines the country’s environment and agricultural calendar. It also brings with it significant hazards. For a quick overview of Nepal’s seasons;

- Winter – Runs from December to February. It is cold and dry in the hills and mountains. High passes often close due to snow.

- Spring – March to May. It is warm and clear. This is trekking season. Humidity increases towards late May.

- Monsoon – June to September. Hot, humid and very wet. Torrential afternoon and evening downpours. 80% of annual rainfall falls in this window.

- Post-Monsoon – October to November. Dry, clear skies, mild temperatures. This is peak trekking season. However, recent years have seen late monsoon creep into October because of climate pattern shifts and warmer sea temperatures…which is exactly what I am experiencing right now.

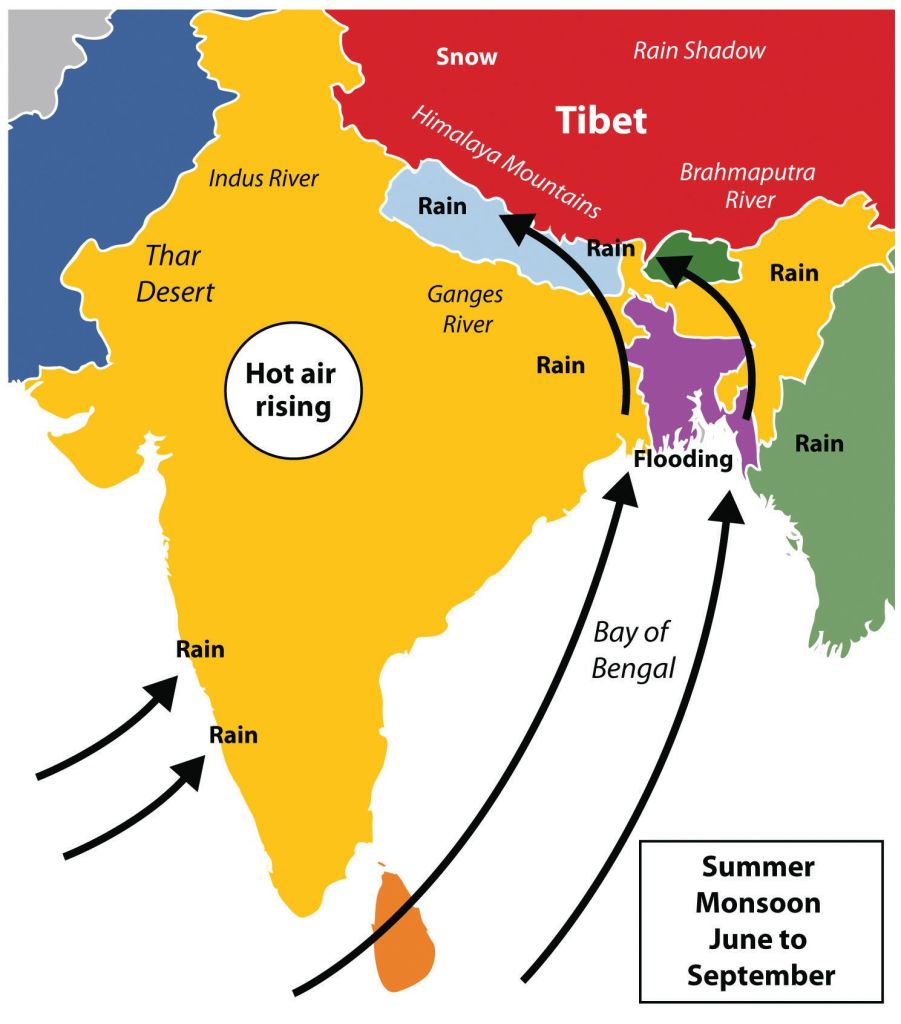

The South Asian monsoon arrives in early June and is driven by moisture-laden winds from the Bay of Bengal that hit the Himalayan barrier. By the peak, in July and August, Kathmandu can see 300-400mm of rainfall per month. The rains are heaviest in the southern Himalayan slopes, whilst the trans-Himalayan regions lie in the rain shadow and stays relatively dry.

With monsoon rains come a variety of hazards. Landslides are common, triggered by saturated slopes and poor drainage and frequently block roads and isolate villages. The highway from Kathmandu to Pokhara (where I am supposed to be heading) frequently experiences landslides. Intense cloudbursts and glacial lake bursts can cause flash floods in the Himalayan valleys. And sometimes landslides can create dams across rivers which fail and cause flashfloods downstream. Infrastructure comes to a standstill when the monsoon is at its most intense. Roads become impassable, and the government may put restrictions on travel. Flights face significant delays. And power cuts and network interruptions are common. Health and sanitation become issues in the worst situations, particularly if drainage overflows into water sources. Deforestation and urban expansion only serve to exacerbate the issues listed above as they result in increased surface runoff.

Then there is the economic impact. The monsoon is vital for rice and millet cultivation, but if the rainfall is too heavy or too weak it threatens the yield. Flooding can wipe out entire fields, and delayed rains can delay planting and shorten the growing season.

In recent years, late-season heavier rainfalls have been observed. This is the most noticeable aspect of climate change affecting Nepal and is linked to warmer Indian Ocean conditions. Warmer water increases evaporation, supplying extra moisture to the monsoon system.

Typically, Nepal’s monsoon withdrawal occurred around the third week of September, when the moisture-laden south-easterly winds begin to retreat towards the Bay of Bengal and the subtropical westerlies reestablishes dry westerlies. What has been observed since around 2010 is that the jet stream has weakened and shifted towards the poles, delaying the reversal of winds and meaning that heavy rains continue well into early/mid October, and can produce record rainfall events. Researchers believe that the South Asian monsoon is experiencing temporal redistribution where rainfall is becoming more concentrated and later in the season. Climate models project this later onset could extend to 5-10 days by mid-century and that more intense downpours will become normal.

As I have seen in almost every country I have visited this year, Nepal is clearly observing climate change and having to adjust quickly to a new normal.

Leave a comment