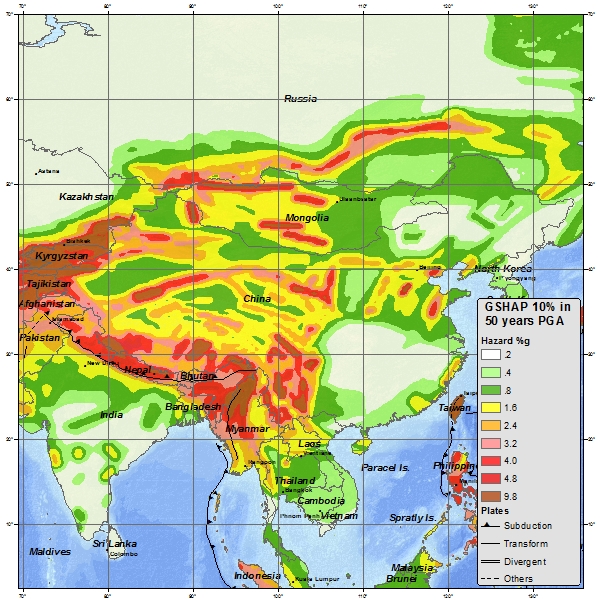

Tibet lies within one of the world’s most tectonically active zones. Earthquake hazard in the region is tied to the ongoing collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates. Active faults criss-cross Tibet, with strike-slip faults in the north and west, normal faulting trending from north to south and thrust faults along the Himalayas. There are frequent Mw 6-7 earthquakes in Tibet, and then a handful of events that exceed this including this year’s Tingri earthquake.

Tibet is also exposed to a number of secondary hazards that accompany large earthquakes. These include landslides and rocks falls triggered in steep valleys and mountain slopes, which can in turn can cause river blockages that might burst. Earthquakes can also destabilize glaciers and trigger glacial lake outburst floods.

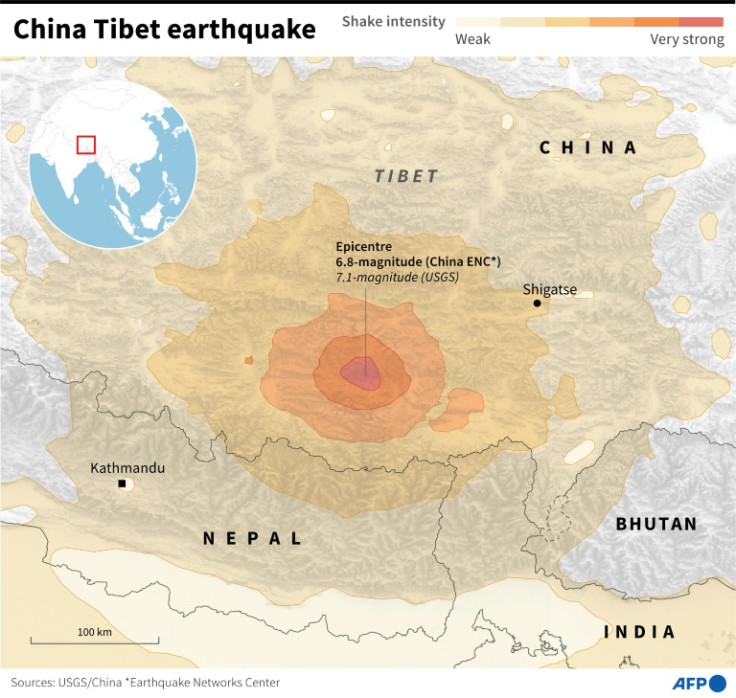

During my time in Tibet we spent a number of days driving through the area that was affected most severely by the January 7th 2025 Tingri earthquake. USGS estimates that the the earthquake had a Mw of 7.1 and shallow focal depth of around 10km. The epicenter was in Tingri County within the Shigatse Province of Tibet (in the south-central) and by a week after the main shock, 3600 aftershocks had also been detected. This is a remote region of the world and the folks who live here are typically farmers with few assets bar their land, their animals and their home.

The damage from the earthquake was extensive. Official Chinese sources reported that there were 126 fatalities and 188 injured, as well as over 3,600 buildings collapsed or heavily damaged. In some villages 80-90% of homes were destroyed. This may seem like fairly small numbers, but when you consider the small population of this part of Tibet, it makes up a significant amount of the population affected. Roads and transport routes were damaged by landslides and subsidence. And 5 dams and reservoirs were found to have cracks or tilting after inspection, resulting in a number being drained as a precaution.

A large scale rescue and recovery operation was mobilized by the Chinese government, which was complicated by the cold, high-altitude environment. Sources indicate that 47,000 people were either temporarily relocated to shelters or provided with makeshift housing. And a central fund was allocated to disaster relief. From what I saw on the ground, the recovery effort is very much underway, but no where near finished. There are still emergency shelters visible in every village that we passed, with people still living in them. But there is a huge amount of construction work on-going. In almost every village we saw cement being poured, windows be fitted and piles of insulation panels ready to be installed. The houses are being re-built using modern materials and techniques but the traditional Tibetan style and design is being retained. They are also being rebuilt to withstand future potential earthquake risk as well to be better insulated in the winter months. The reconstruction effort seems extensive across the region and impressive. Every village was somewhere in the process of recovery.

It was interesting to see a reconstruction effort first-hand. Typically when a big event like this happens it will appear in the news for a few days, but slowly the news coverage will decrease until it is no longer talked about. But recovery and reconstruction can last for years and be a very slow process, especially in remote and less well-off areas. Consider that the border crossing between Tibet and Nepal took 4 years to re-open after the 2015 Nepal earthquake. And that the emergency tents distributed by the government in January this year were still being actively lived in 8 months later.

Leave a comment