Kyrgyzstan is one of the most tectonically active regions in Central Asia. Similar to the reasoning I provided for the high seismic risk in the south and south-east of Kazakhstan, the majority of Kyrgyzstan lies in the Tien Shan mountain range, where the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates are converging. There are several major faults that cut right through the country, notably the Talas-Fergana fault and the Issyk-Ata fault.

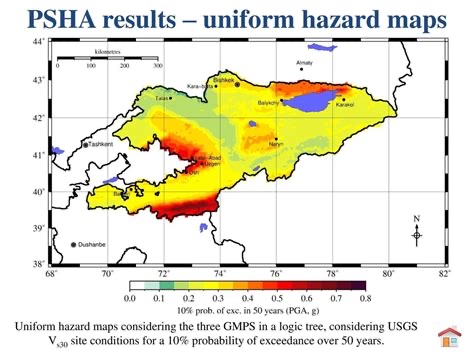

Seismic studies that have used open source probabilistic models like the Global Earthquake Model (GEM) and OpenQuake indicate a Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA) (this value tells us how hard the ground is expected to shake during an earthquake) ranging from 0.1g in the northwestern regions of the country to 0.4-0.6g or higher in the south and the mountainous regions. In layman’s terms 0.4-0.6 g is considered to translate to severe shaking with widespread damage and a need for that area to invest in earthquake-resistant construction. For comparison, Japan, California and Taiwan have similar PGA values in their most high-risk areas. The earthquake hazard is considered high in Bishkek and extremely high in both Osh and the mountain region I have been travelling through.

Kyrgyzstan has had at least 4 earthquakes with a magnitude greater than 7 in the last 150 years, plus many in the 6+ magnitude range.

- The 1885 Belovodskoye earthquake near Bishkek that caused severe shaking across the Chuy Valley and was estimated at 6.9-7.6 in magnitude

- The 1911 Kemin earthquake in the Chuy Valley, measure 8.0, one of the largest ever recorded in Central Asia and causing a huge 200km surface rupture

- The 1946 Chatkal earthquake in western Kyrgyzstan, felt across the Fergana valley at 7.5-7.6 magnitude

- The 1992 Suusamyr earthquake north of Toktogul with thousands of buildings damaged at 7.3 magnitude

It is estimated if a magnitude 7.5 earthquake were to happen on the Issyk-Ata fault that lies close to Bishkek, then there would be tens of thousands of buildings damaged, either completely or partially. And undoubtably thousands of people would lose their lives.

The secondary hazard of landslides and rockfalls is very common in the mountainous areas of the country and are frequently triggered by seismic activity. Areas that have had landslides in the past were easy to spot along the drive we have taken over the last couple of days, as well as gigantic rocks that have tumbled down the mountain side.

Both the 1946 Chatkal earthquake and 1992 Suusamyr earthquake caused hundreds of landslides and rock avalanches, burying villages and roads. The communities in these areas are rural and very isolated, exacerbating the impact these secondary hazards have when they cut off essential roads. Quake lakes and flooding are also common in the region, with landslides damming rivers and forming temporary lakes that then fail resulting in catastrophic downstream floods.

In addition, because Kyrgyzstan has very high mountains that are heavily glaciated there is the additional risk of glacial lake outburst flooding and ice avalanches, if moraine-dammed lakes fail. An example of this is the 1992 Suusamyr earthquake.

There is also a growing concern over nuclear waste tailings stored behind unstable dams in the Fergana Valley area. There is a worry that an earthquake could destabilise the dams and result in catastrophic radioactive contamination of farmland and water systems across Central Asia. For a little background – during the Soviet era, uranium was milled and mined in the Fergana Valley across Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. The waste was stored in dams and dumps along rivers that flow into the Syr Darya river. This river irrigates the densely populated and heavily farmed Fergana Valley region of around 16 million people. If radioactive sediment was swept down into this river it would be catastrophic across all three countries.

Reports indicate that there are about 700,000m^3 of waste at risk from landslides and earthquakes. This is not a ‘what if’ scenario as there have already been small incidents in 1958 and 2002 when thousands of cubic meters were released accidently. These incidents also highlight the cascade effect of earthquake to landslide to flood. Clean-ups are being financed by the Environment Remediation Account for Central Asia with help from the EU but it is going to take a lot of money and time. This type of hazard is a good example of systemic risk, where the whole economy of a region could collapse if the worst were to happen.

All of Krygyzstan’s major cities sit near active fault lines and have very large inventories of unreinforced masonry structures. The country does have seismic-resistant building code standards, but enforcement is inconsistent, particularly in rural areas. Retrofitting older buildings is being prioritised for vulnerable public infrastructure likes schools, hospitals, bridges and hydropower plants. And large dams are being strengthened to withstand stronger ground shaking. There are specific organisations monitoring unstable slopes in highly populated areas through both satellite and drone surveys. And engineering interventions in landslide-prone valleys like Mailuu-Suu. Some lakes are being artificially drained to a lower depth in order to reduce the risk of dam bursts.

However, all these retrofitting measures are costly and the country has limited resources. The country is also one of the most mountainous in the world (94% of its territory is classed as mountains) and almost entirely covered by the Tien Shan and Pamir Alai mountain ranges. It is impossible to monitor and take action across such a huge area effectively. The country does have a seismic monitoring network and can issue warns to emergency services within a few seconds, however there isn’t a system to alert the public yet. For valleys at high-risk of landslides and flooding, there are ground sensors, cameras and sirens installed to alert local communities if a slope starts to move.

The country has also introduced a national emergency SMS alert system that can broadcast warning messages to phones, although in remote valleys there is often not reliable signal. Schools also run drills and education sessions to students. Many international organisations are providing support and funding including the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. There are also initiatives like the Global Earthquake Model that look to provide earthquake hazard assessments for countries that do not have commercial probabilistic earthquake models available.

Leave a comment